by Jean Marie Carey | 7 Oct 2010 | Animals, Animals in Art, Dogs!

Landscape with Snow

Vincent Van Gogh’s Landscape With Snow (1888) is a bit of an oddity amid the nearly 200 paintings Van Gogh made during his relatively brief (fifteen months) but exceedingly productive sojourn to the outskirts of Arles, France, following his immersion in Parisian café culture. As with the canvas depicting the storm on the shore at Scheveningen, Landscape With Snow seems to have recorded a real weather event, a heavy and rare blizzard that happened just as Van Gogh arrived in what he must have been surprised to find was not a sunny early spring day in the south of France. Of greater interest for my research, however, is the rare appearance of an animal – a dog – in this painting.

The dog and his man are walking away from the viewer, and the painter, on the left side of the raised rut between a slushy dirt road and an adjacent fallow field, also patched with snow and maybe ice, though the cold and precipitation seems not to have discouraged the emergence of a few early bursts of foliage. The sky overhead is the cold grey of a European late afternoon, but the village, not too far distant, offers the shelter of steadfast trees and some inviting-looking structures. Still it is the presence of the dog that lends this canvas a sense of comfort – the man and the dog are just out walking and will soon reach the village – rather than the foreboding and isolation a solitary figure would indicate.

Vojtech Jirat-Wasiutynski describes Van Gogh’s fascination with Arlesian agrarian labor practices (and the impingement upon those practices as evidence by the occasional appearance of modern machinery) in a way that echoes Griselda Pollock’s pieces (supported by an even greater amount of first-source historical data) about Van Gogh and the peasant population around Nuenen. Both scholars more than suggest that Van Gogh was a bit clueless as to the actual monotonous particularities of the type of manual labor required by life on a farm, with or without the assistance of efficiency-making devices. However, while Pollock’s interest in Van Gogh is more or less in envisioning the social practices of capitalism realized in painting with the painter as the generalized fulcrum, Jirat-Wasiutnski concentrates on a favorable understanding of Van Gogh’s intentions. I say intentions because while Jirat-Wasiutnski intuits a good bit of bonhomie from Van Gogh’s visions of companionship with like-minded artists as he imagined existence in Japan and an almost Futurist-like faith in the benefits of embracing modernity, the landscape paintings do not precisely, in many cases, reflect this sense of community and optimism. In fact despite its chilly setting, Landscape With Snow (because of the dog) is much more emotionally vibrant than, for example, the invitingly titled but simultaneously cluttered and barren Orchard With Blossoming Apricot Trees (1988) from just one month later.

Flying Fox

My favorite Van Gogh painting, period, is Flying Fox (1885) from the Nuenen period. I have always wondered why, after so viscerally animating a creature he could never have seen when it was alive and in its natural environment, Van Gogh’s interest never again turned intensively to the many available creatures of the earth in Nuenen, Paris, and Arles who invited the same types of projections of innocence and typicality as the peasants, fieldhands, and café attendants Van Gogh was so fond of. Franz Marc saw something in Van Gogh’s work that made the German painter immediately embark on his canonical horses. I am still curious and will continue to search for whatever this galvanizing influence is.

See: Vojtech Jirat-Wasiutynski, “A Dutchman in the South of France: Van Gogh’s Romance of Arles,” Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. (78-89)

by Jean Marie Carey | 24 Jan 2010 | Art History

York University art history professor Carol Zemel’s overall project with respect to Vincent Van Gogh is an ambitious one, as she suggests that (among other sub-theses) Van Gogh was a somewhat pragmatic, business-oriented artist in complete, even distancing, control of his artistic product until the final few months of his life, a view that usurps his mythology. In the chapter of her 1997 book, Van Gogh’s Progress: Utopia and Modernity in Late-Nineteenth-Century Art titled “Modern Citizens: Configurations of Gender in Van Gogh’s Portraiture,” Zemel further identifies Van Gogh’s strategies and seems to suggest that external factors – the changing role of women in society, the conflict between burgeoning modern life and Van Gogh’s concept of agrarian utopia, and the shift of identifiable classed and gendered roles in general – contributed more greatly to Van Gogh’s ultimate breakdown than underlying biological mental illness.

(more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 21 Oct 2009 | Art History

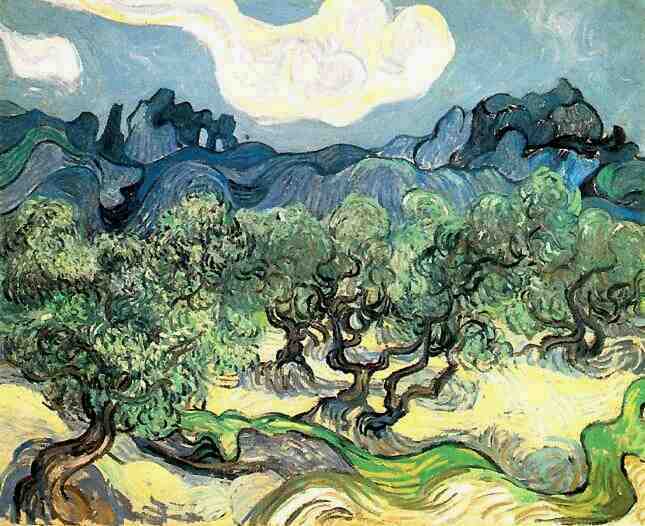

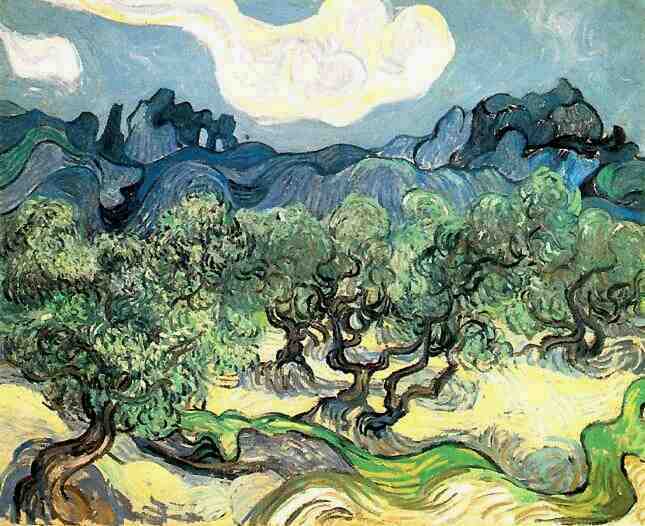

Van Gogh scholars Vojtěch Jirat-Wasiutyński and Joan Greer present comparative views – comparative in the sense that some aspects differ and some also agree – of Vincent Van Gogh’s production of olive-tree related paintings during his slightly-longer-than-one-year stay in Saint-Rémy beginning in May 1889 in the respective articles “Vincent van Gogh’s Paintings of Olive Trees and Cypresses from St.-Rémy” and “A Modern Gethsemane: Vincent Van Gogh’s Olive Grove.” While both pieces emphasize the storied Biblical association of olive trees and olive groves and explore various aspects of Van Gogh’s perception and representation of himself as a Christic figure, Greer brings forward some interesting arguments concerning Frédéric Salles, a Reformed Church minister who visited Van Gogh at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole and became involved with the artist and his family, and about the possibility of Van Gogh’s intentions around these paintings to engage in a sort of conversation with Emile Bernard and not-so-subtle reproach to Paul Gauguin about observation vs. memory studies and religious iconography. Jirat-Wasiuty?ski proposes as an aside that Van Gogh’s cypresses constitute references to Egyptian art (as invocations of immortality) and that the olive series also furthered Van Gogh’s earlier pursuit of typology and physiognomy in attempting to locate the nostalgic and essential in Provencal culture. Finally, Vojtěch Jirat-Wasiutyński makes some points about Van Gogh’s identification olive and cypress trees not as religious symbols but as relatable organisms. “Both trees were treated as tough outcasts, relegated to marginal land,” Vojtěch Jirat-Wasiutyński observes on page 650.

Greer is persuasive in her account of Salles’s appearance in Van Gogh’s life as a sympathetic figure and one whom Van Gogh could fix some of his yearning for connection upon and as a vector for rekindling connections to Protestantism. Viewed this way, Van Gogh’s representations of himself as a Christ seem more grounded in the longstanding tradition of post-Reformation artists to show themselves this way (such as Albrecht Durer’s most famous self portrait). This type of representation springs not from hubris, but from the belief that man is made in God’s image. Speaking of hubris, though, this does not account for Gauguin’s Christic delusions (coming from a Catholic family it is further mortifying to learn that Gauguin also poorly represents us – this man is a constant disappointment on every level). As to Van Gogh’s dialogue with Bernard and Gauguin, certainly this is a possibility – Van Gogh probably (in reference to conversations which may have taken place in Paris) entertained the hope of “getting the band back together.” (more…)