by Jean Marie Carey | 25 Sep 2008 | Art History

“Enraged by Tea,” one of my all-time photophone favorites, from 2005.

The three essays discussed in this response paper relate to contemporary concepts around the analysis of visual culture through the interpretation of the philosophies of history, commodification, and language as refracted by The Man’s capitalistic hijacking of the involuntary human practice of looking.

While Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels use the terminology typically associated with the social proposals of communism including the expected references to the “proletariat” and the “bourgeois,” these selections from German Ideology constitute less a political manifesto than an intellectual proposal for the active reconfiguring of the recording and interpretation of history. Marx and Engels (and, for the consideration of these works, Barthes) are not particularly known for easily comprehensible prose styles. German Ideology capitalizes, so to speak, on the even more opaque writing of the greatest German ideologue of the time, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Marx and Engels propose that while there is some fundamental correctness to the Hegelian principle of the dialectic – ascertaining an absolute truth through logical dissection and argument – historians and philosophers following Hegel had simply got everything wrong. Rather than intangible evolved yearnings for “immanence” and “transcendence,” humanity is a material manifestation controlled by economics. This definition of “historical materialism” is preceded by “dialectic materialism,” which establishes both the sole existence of the physical (as opposed to ephemeral) world, and, more significantly in connection to visual culture studies, the establishment of the thesis/antithesis paradigm which eventually becomes known as “binary opposition.” (Marx – more Marx than Engels – also takes exception to other “Hegel deconstruction” scholars such as Ludwig Feuerbach and Max Stirner). In a certain titular and textual respect, these selections undercut some of the assumptions endemic to the concepts of alterity politics and false constructions of Otherness raised during the heights of Post-Modernism simply by presuming that such a thing as an ideology based not upon colonial dynamics or Western European cultural dominance but on the national identity of Germans.

(more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 13 Jun 2008 | Art History, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

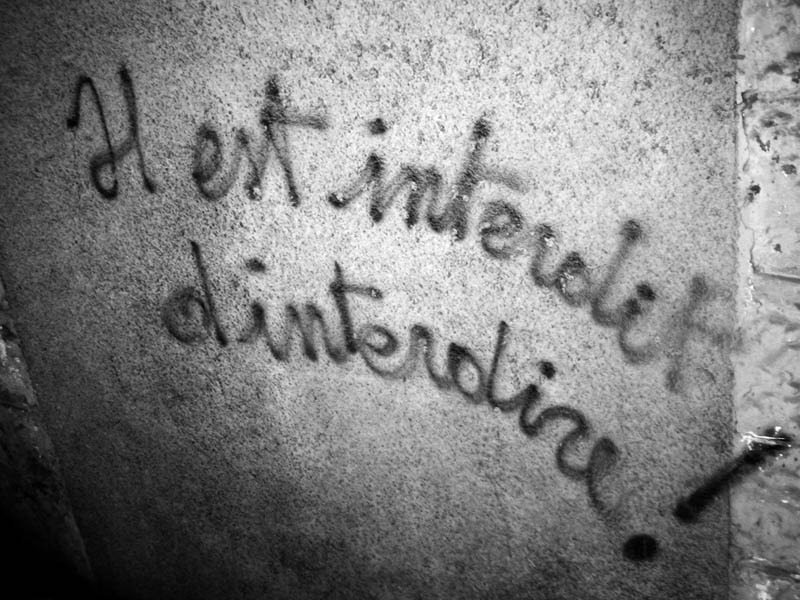

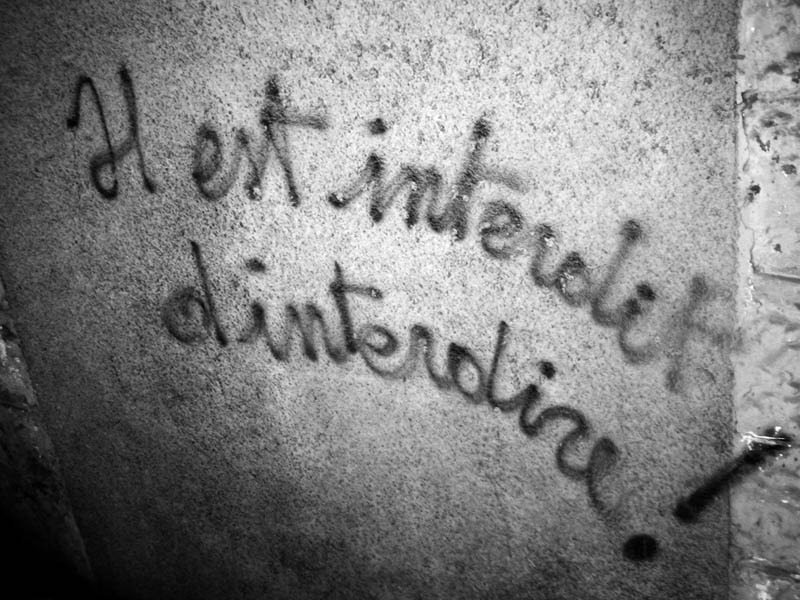

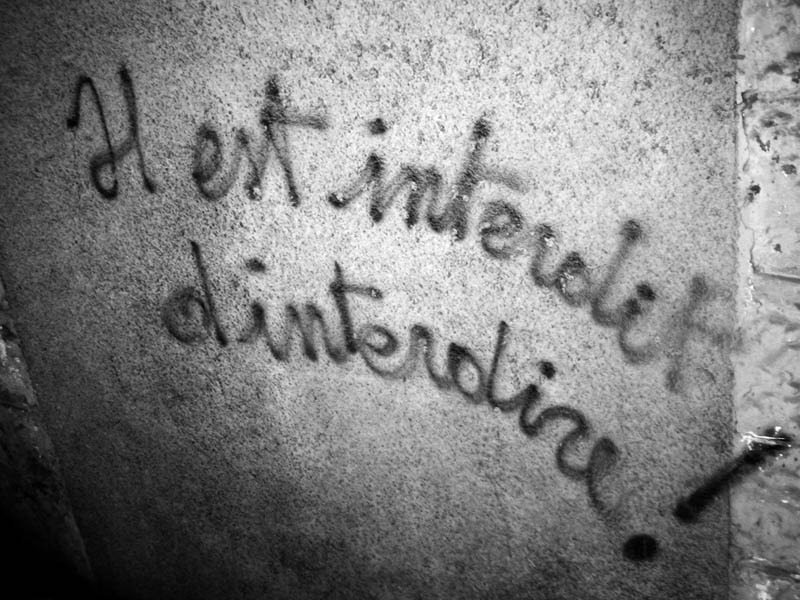

Situationist grafitti, Menton, Occitania, 2006 (the 1968 slogan “It is forbidden to forbid”, with missing apostrophe). Wikipedia Commons

Situationist grafitti, Menton, Occitania, 2006 (the 1968 slogan “It is forbidden to forbid”, with missing apostrophe). Wikipedia Commons

“Rather — just as certain biologists argue for the maintenance of species diversity among plants in order to preseve them for potential use by future generations — we should battle on the side of the obscure, the small, the powerless, the marginalized in order to maintain bio-diversity of memes, of ideas and aesthetic and imaginary realms.”

Marina LaPalma’s “Situationism: A Primer” is one of the best readings in existence for art history students because it is very easy to digest, in terms of distilling the much more difficult prose of situationists from the 1960s, particularly Guy Debord, but also because it is a call to action that clearly illuminates some of the social conditions to be acted against.

Written in 1988 in honor of the approximate twentieth anniversary of the publication of The Society of the Spectacle, “Primer” notes that the intervening decades have made DeBord’s observations seem even more absolutely correct. (Time has done the same for “Primer.”) LaPalma describes a completely dystopic society, yet in the last quarter of the article makes clear that her intent overall mood is hopeful.

Like the original SI group, LaPalma makes a few incorrect assessments, identifying simple sociopathy (“Can any pleasure we are allowed to taste compare with the indescribable joy of casting aside every form of restraint and breaking every conceivable law?”) and the Los Angeles riots as appropriations of situationism.

Yet many – most – of LaPalma’s statements about the Spectacle, like DeBord’s, seem even more valid today than when written: “The world we see is not the real world, it is the world we have been conditioned to see; a world constructed from the black and white of tabloids, a world framed by the mahogany veneer of the television set, a world of carefully constructed illusions – about ourselves, about each other, about power, authority, justice and daily life. A view of life from the perspective of power.”

LaPalma uses the commodification of superficially “rebellious” music (punk and techno) to illustrate the idea of recuperation, and is also, mercifully, extremely critical of hippie-collectivist modes of dropping out. “Revolution is a process, a process that can be started now,” says LaPalma.

The problems – isolation through the work/home/consumer system, totally immersive media that purports to broadcast reality, the replacement of the citizen by the consumer – are clear. The extremity of the endless war, continuous states of celebrity meltdown, and now, recession, makes action seem like the only choice. LaPalma does not provide any guidance for resisting the Spectacle within society without perpetuating it.