by Jean Marie Carey | 21 Jan 2015 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, August Macke, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Helmuth Macke, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

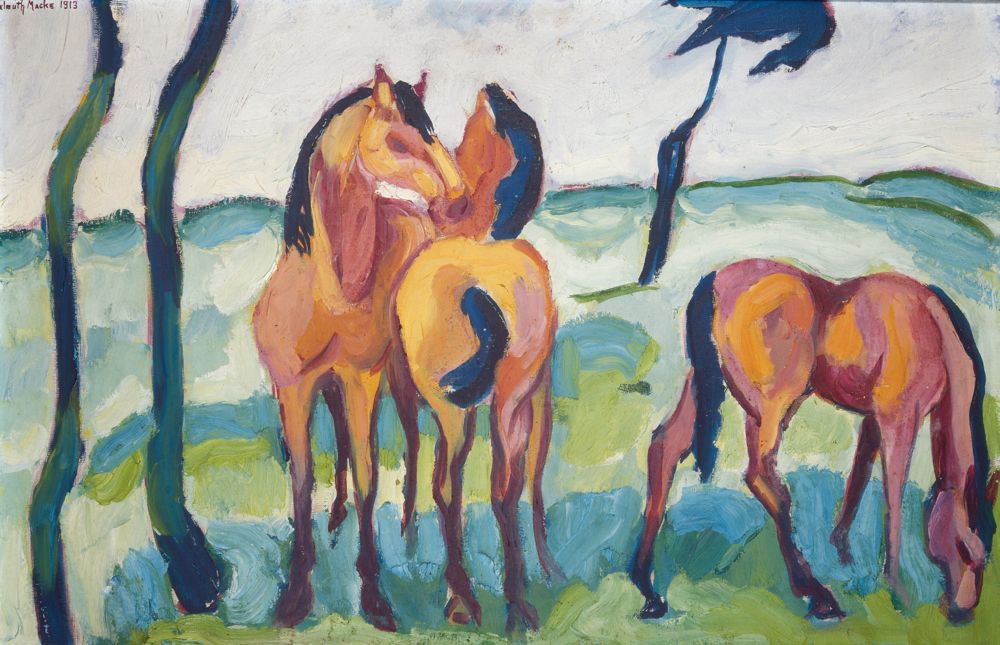

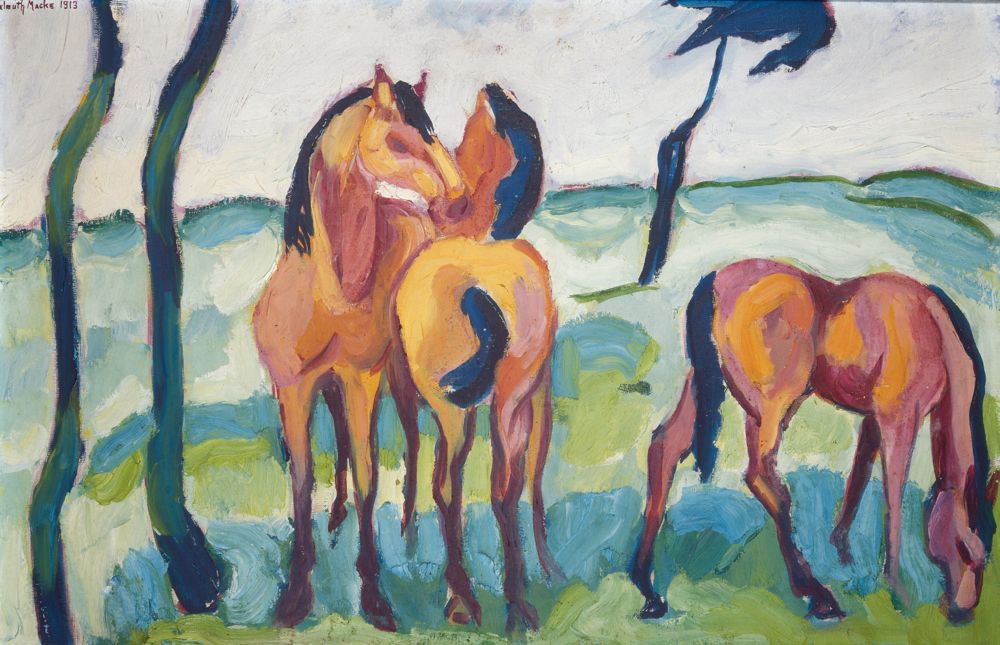

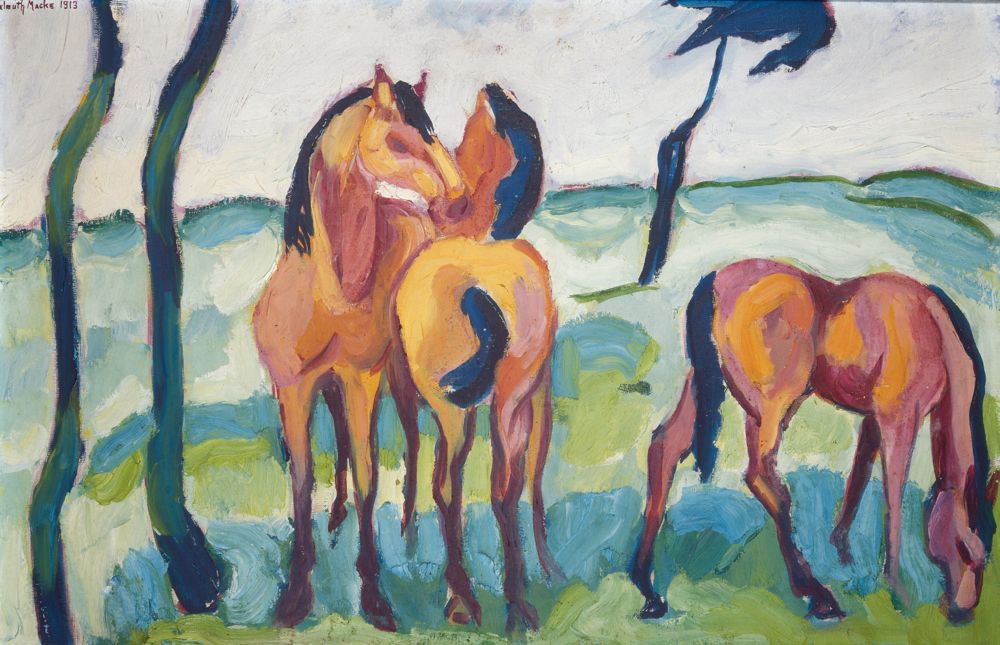

Helmuth Macke,

Drei Pferde,

1913

“The ‘boarding school’ is in session,” Franz Marc wrote nervously to his friend August Macke.[1] Pining for company in the same letter, Marc nonetheless wondered if August should come and get Helmuth Macke, August’s young cousin, whom the Macke family had deposited some weeks earlier at Marc’s small apartment in rural Sindelsdorf. It was late November 1910. Marc would soon turn 31, and Helmuth was 18. Until Helmuth’s arrival, Marc had been working alone for some time. At the insistence of her concerned parents, Maria Marc had returned to Berlin. Marc was just beginning to see the slightest of incomes from his painting, but he was irritable and distracted. And now August, himself adjusting with his wife Elisabeth to the birth of their son, expected Marc to find ways to entertain a teenager.

Yet Helmuth was resourceful and clever. During the weeks in Sindelsdorf, (which become months and longer: “Helmuth’s fine, he’s still growing,” Marc reported the following summer)[2], Helmuth taught himself enough Dutch to communicate with Heinrich Campendonk; chopped wood and built a fence; practiced painting and drawing, befriended Marc’s dog Russi; and demonstrated a talent for cooking and baking. This latter skill commanded Marc’s particular favor. Animated but sympathetic, Helmuth provided stability and encouragement. By Christmas Marc had breezily informed August that Helmuth would be staying on.[3]

As the calendar turned to 1911, the chrysalis of Sindelsdorf opened and released a new Marc to Munich. Seeking a sophisticated way to celebrate New Year’s, Helmuth pointed Marc toward a performance of Arnold Schönberg quartets. The music had a vivid impact on Marc, which he reported with great excitement to Maria, August, and a new friend who had missed the concert – Wassily Kandinsky. At a the soirée given by Marianne von Werefkin at which Marc and Kandinsky met at last in person, Helmuth was at Marc’s side, and witnessed the twinkle in the eye of fate that became Der Blaue Reiter.[4]

After the party, Helmuth and Franz took the late train from Munich to Penzburg, laughing and marveling over their adventure as they walked jauntily through the falling snow back to Sindelsdorf. Neither traveler was concerned for the future at that joyful moment, and mercifully, neither could know what the future held.

Helmuth Macke died in 1936 when his small boat capsized in a sudden storm on Lake Constance, having given his sailing companion the only life preserver.

[1] Franz Marc, August Macke: Briefwechsel. (Köln: DuMont, 1964), 20-21.

[2] Marc and Macke: Briefwechsel, 42.

[3] Marc and Macke: Briefwechsel, 28.

[4] Dominik Bartmann, Helmuth Macke, (Recklinghausen: Verlag Aurel Bongers, 1980), 26.

by Jean Marie Carey | 28 Jul 2014 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL

Brigita Hofer cleans, fills, patches, and recolors “Paradies.”

Here is a short article on the ruhr.de website about the restoration of the Paradies mural made by Franz Marc and August Macke in 1912 at the Mackes’ home in Bonn. It’s an interesting little piece and the website also has some photographs of the movement of the mural, in the 1980s, from its original location to the Museum für Kunst ind Kultur/Westfälisches Landesmuseum in Münster, where it lives today (there is a pretty nice replica at the August Macke Haus though). Like a lot of people I am sad that the museums can’t just switch the murals back, but this article sort of explains why that will not happen.

The restorer, Brigita Hofer, has discovered that the mural is pretty structurally unsound, giving it a soundness rating (as happens with earthquake-damaged buildings as I recently learned) of around 25, which means there’s a better than one in four chance it could collapse under any further stress. Hofer has been filling in surface cracks and erosions with non-expanding plaster and emulsifier with the tiniest of syringes. Hofer also restored some of the mural’s damaged or faded paint. In doing so she discovered that Macke and Marc had made a lot of adjustments to the mural as they worked together, repainting Eve’s face and the deer. Hofer also learned from a heretofore covered note that Maria Marc had painted the wasp at the bottom of the mural.

I am fascinated with this mural, as you might guess from how often I write about it, not for the least reason that it seems to be a truly collaborative effort that resulted in a distinct “style” that is identifiably that of both painters but is also a unique meshing of their ideas and talents. Even the animals don’t look exactly like Marc’s other animals, and for both, the palette is a bit subdued. (Except Adam reaching to embrace the monkey on the top left branch though and turning from the other figures – I think that’s a Marc thing. There is a large image of the mural in the post just before this one.)

by Jean Marie Carey | 15 Jun 2014 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

August Macke and Franz Marc packed the friendship of a lifetime into the few short years they had together from early 1910 to the summer of 1914, even with a few breaks for pouting and sulking. Some of their correspondence is recorded in a dedicated volume, and other letters, notes, stories, and recollections of their doings from other people are hidden in unpublished works and Expressionist apocrypha.

Macke and Marc enjoyed working on their art as a pair and in fact they both considered the drawings and sketches they made while just being together to fall into the class of “things we made together” on the same level as the few categorical objects to which we ascribe to their dual provenance, of which the mural Paradies, from 1912, is one. The mural lives now at the Westfalisches Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kultur in Münster, but it was made in the upstairs atelier of the Macke house (now the August Macke Haus ) in Bonn.

Given Macke’s constant scheming and hustling, and the sort of declarations of superficiality he seems to make about all that is admirable in painting, it is easy to think of him as being a sort of light shadow to Marc’s heavy element, but this is not at all true. And Marc often seems supremely naïve and dopey in his out-of-itness, which was also more of an occasional condition. However, the story attendant to the making of this mural finds them both in exactly these roles.

In fact as soon as I learned more about how Paradies was made, I immediately thought of the famous story in Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer printed below. In fact there is not much I can say about it, or as well.

Paradies, August Macke and Franz Marc, 1912

Excerpt from Tom Sawyer: Chapter 2

“Hi- yi ! You’re up a stump, ain’t you!”

No answer.

Tom surveyed his last touch with the eye of an artist, then he gave his brush another gentle sweep and surveyed the result, as before. Ben ranged up alongside of him. Tom’s mouth watered for the apple, but he stuck to his work. Ben said:

“Hello, old chap, you got to work, hey?”

Tom wheeled suddenly and said:

“Why, it’s you, Ben! I warn’t noticing.”

“Say — I’m going in a-swimming, I am. Don’t you wish you could? But of course you’d druther work — wouldn’t you? Course you would!”

Tom contemplated the boy a bit, and said:

“What do you call work?”

“Why, ain’t that work?”

Tom resumed his whitewashing, and answered carelessly:

“Well, maybe it is, and maybe it ain’t. All I know, is, it suits Tom Sawyer.”

“Oh come, now, you don’t mean to let on that you like it?”

The brush continued to move.

“Like it? Well, I don’t see why I oughtn’t to like it. Does a boy get a chance to whitewash a fence every day?”

That put the thing in a new light. Ben stopped nibbling his apple. Tom swept his brush daintily back and forth — stepped back to note the effect — added a touch here and there — criticised the effect again — Ben watching every move and getting more and more interested, more and more absorbed. Presently he said:

“Say, Tom, let me whitewash a little.”

Tom considered, was about to consent; but he altered his mind:

“No — no — I reckon it wouldn’t hardly do, Ben. You see, Aunt Polly’s awful particular about this fence — right here on the street, you know — but if it was the back fence I wouldn’t mind and she wouldn’t. Yes, she’s awful particular about this fence; it’s got to be done very careful; I reckon there ain’t one boy in a thousand, maybe two thousand, that can do it the way it’s got to be done.”

“No — is that so? Oh come, now — lemme just try. Only just a little — I’d let you , if you was me, Tom.”

“Ben, I’d like to, honest injun; but Aunt Polly — well, Jim wanted to do it, but she wouldn’t let him; Sid wanted to do it, and she wouldn’t let Sid. Now don’t you see how I’m fixed? If you was to tackle this fence and anything was to happen to it — ”

“Oh, shucks, I’ll be just as careful. Now lemme try. Say — I’ll give you the core of my apple.”

“Well, here — No, Ben, now don’t. I’m afeard — ”

“I’ll give you all of it!”

Tom gave up the brush with reluctance in his face, but alacrity in his heart. And while the late steamer Big Missouri worked and sweated in the sun, the retired artist sat on a barrel in the shade close by, dangled his legs, munched his apple, and planned the slaughter of more innocents.

by Jean Marie Carey | 8 Feb 2014 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

Tierschicksale, 1914, Franz Marc

Was kann man thun zur Seligkeit als alles aufgeben und fliehen? als einen Strich ziehen zwischen dem Gestern und dem Heute? – Franz Marc, February 1914, from the intended introduction to the second edition of the Blaue Reiter Almanac. First printed in Der Blaue Reiter. Dokumentarische Neuausgabe by Klaus Lankheit. München, 1965, p. 325.

One of the most frequently cited articles about Franz Marc in popular literature is Frederick S. Levine’s “The Iconography of Franz Marc’s Fate of the Animals” from a 1976 issue of The Art Bulletin, and, subsequently, a short book on the same subject. Apparently there are some issues with the accuracy of the translations presented in both. What’s interesting to me is the creative idea Levine had to analyze Marc’s enormous 1913 painting Tierschicksale (mysteriously residing in the Kunstmuseum Basel) as an expression of Ragnarök, the apocalypse of Norse mythology. My opinion is that despite being generally familiar with the Eddas and with Der Ring des Nibelungen Marc wasn’t that interested in these sagas and didn’t consider them as particularly German.

A few years ago Andreas Hüneke, researching at the Lenbachhaus, discovered that the inscription on the back of the painting, „Und alles Sein ist flammend Leid“ is from a volume of the Buddhist Dhammapada of the Pali Canon of Buddha Siddhartha Gautama given to Marc by Annette von Eckardt. So it doesn’t seem to refer to Ragnarök directly as Levine (not having the benefit of Hüneke’s recent work) asserts. It seems more likely that Marc was very distressed, in the summer of 1913 when he made Tierschicksale, about von Eckardt’s move away from Munich to Sarajevo. It explains a little bit about why, upon seeing the painting again a few years later, Marc says he doesn’t even remember creating it and ascribes its meaning to the more external conflagration at hand.

In any case, Levine was not discouraged by his translating experience and went on to the faculty at Palomar College in California and also spent a lot of time studying and teaching at the University of Tasmania in Hobart.

Today, on Marc’s birthday, with so many animals imperiled, Tierschicksale doesn’t really need any overdetermining; it would be very tempting to just turn and flee, if only there was somewhere to go.

by Jean Marie Carey | 20 Jan 2014 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Dogs!, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

Liegender Hund im Schnee, Franz Marc, 1911

“… Du kannst Dir kaum vorstellen, wie wunderbar schön der Winter in diesen Tagen hier ist, schleierloses Sonnenlicht und dabei den ganzen Tag Rauhreif; sehr kalt, aber von jener schönen, erfrischenden Kälte, die einen nur äußerlich, nicht innerlich frieren macht. … Gegen Abend wird es chromatischer, statt blau weiß treten rosa und komplementär grünliche Töne auf, auch violett gegen farbige Abendluft. Ich habe zwei Sachen im Schnee in Arbeit: die Rehe unter schneebedeckten Ästen und den Russi im Schnee liegend. Ich komme mit beiden ganz gut weiter, sehr farbig. …”

Franz Marc, 17.1.1911