by Jean Marie Carey | 28 Jul 2016 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

Franz Marc’s mysterious nude in a landscape from around 1911.

In clear contrast to the well-planned execution of the grazing horses on its front, the verso of Weidende Pferde IV is wild, mysterious, and haunting, and provides an intimate look at Franz Marc’s more intuitive approach to color and form.

Though the composition is partially obscured, the underlying motifs are clear enough.

Shown is a reclining female nude in a dimly lighted landscape under a deep blue sky. The figure rests on her back, her right leg is bent. Her head with long and flowing red hair is slightly tilted to the right; her arms clasped behind her. This figure is somewhat characteristic for Marc in terms of the visible hatching and decorated, colorful outlines. The left of the picture area seems to indicate another figure whose gender and position we can only guess at. The middle of the picture consists of a dramatic, deeply-hued landscape, which in turn is what the reclining nude in the foreground would be part of and also looking at. Though Marc often painted nude figures relaxing outside, this painting does not seem to correspond to another finished work.

Weidende Pferde IV, 1911

Weidende Pferde IV is also a stunning picture when considered in terms of Marc’s efforts to produce it: Three red horses with purple mane prance against a lemon-yellow sky and a deep blue rock formation. Marc had devoted a lot of time to developing the arrangement of the horses’ bodies in this formation. Marc had been preoccupied, and had made a difficult and lengthy process of, how exactly to balance the shapes and colors of the horses in the overall composition.

Weidende Pferde IV is the star of the second part of the exhibition trilogy “Franz Marc: Zwischen Utopie und Apokalypse,” presented by the Franz Marc Museum in Kochel on the 100th anniversary of the death year of the painter. This is one of just a few paintings that Marc saw hung in a museum himself, following its creation in 1911 and first display at the Thannhauser’s Galerie Moderne in Munich

The same year the collector Karl Ernst Osthaus purchased Weidende Pferde IV for the Folkwang Museum’s first incarnation in Hagen. The painting sold for 750 marks, as Marc triumphantly informed his brother Paul on 3 December 1911.

Marc had been constantly busy with live horses during his years in Kochel and Sindelsdorf (“Pferde auf Bergeshöh gegen die Luft stehend”), and he studied them in detail as he drew, printed and painted them.

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1909

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1910

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1910

The day before Alexej Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin and Adolf Erbslöh first visited Marc in Sindelsdorf on 3 February 1911, he wrote to Maria Marc who had at this time had left Bavaria to stay with her parents in Berlin, “Ich habe noch ein großes Bild mit 3 Pferden in der Landschaft, ganz farbig von einer Ecke zur anderen, angefangen, die Pferde im Dreieck aufgestellt. Die Farben sind schwer zu beschreiben. Im Terrain reiner Zinnober neben reinem Kadmium und Kobaltblau, tiefem Grün und Karminrot, die Pferde gelbbraun bis violett.”

The visitors loved the paintings, and by the day of his 31st birthday on 8 February Marc was a co-chairman of Neue Künstlervereinigung München.

Certainly the powerful painting of the reclining redhead should be regarded as an entirely discrete creation and given a proper name and place in the artist’s catalogue raisonné. It is curious that Harvard University’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, which purchased the painting when it was declared Entartete Kunst in 1937, has not taken the initiative to see that this is done. If only this painting could be permanently repatriated to Kochel, where it belongs.

by Jean Marie Carey | 21 Jan 2015 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, August Macke, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Helmuth Macke, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

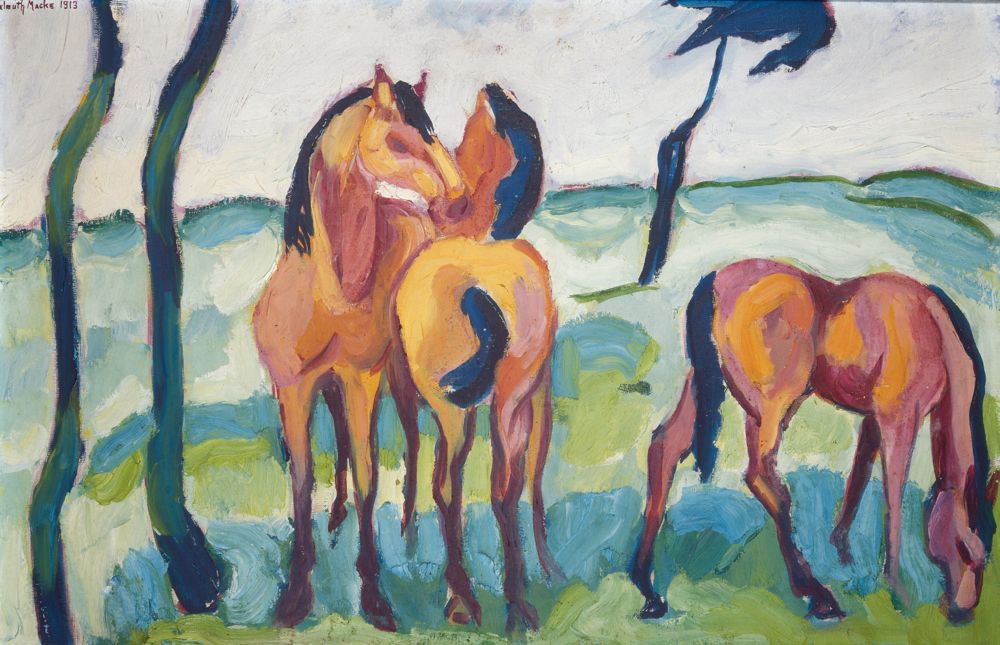

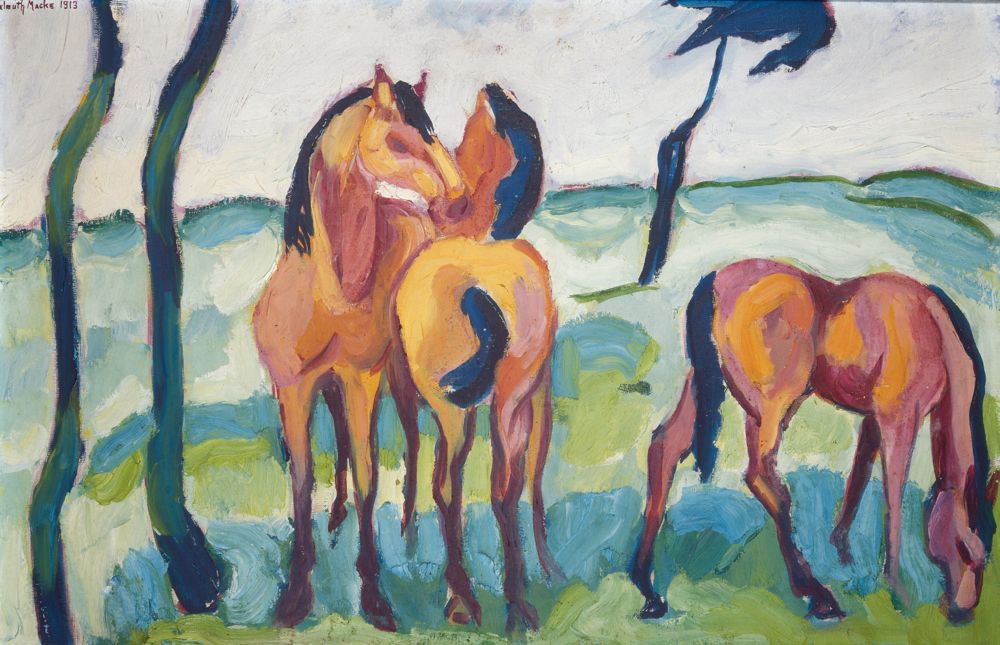

Helmuth Macke,

Drei Pferde,

1913

“The ‘boarding school’ is in session,” Franz Marc wrote nervously to his friend August Macke.[1] Pining for company in the same letter, Marc nonetheless wondered if August should come and get Helmuth Macke, August’s young cousin, whom the Macke family had deposited some weeks earlier at Marc’s small apartment in rural Sindelsdorf. It was late November 1910. Marc would soon turn 31, and Helmuth was 18. Until Helmuth’s arrival, Marc had been working alone for some time. At the insistence of her concerned parents, Maria Marc had returned to Berlin. Marc was just beginning to see the slightest of incomes from his painting, but he was irritable and distracted. And now August, himself adjusting with his wife Elisabeth to the birth of their son, expected Marc to find ways to entertain a teenager.

Yet Helmuth was resourceful and clever. During the weeks in Sindelsdorf, (which become months and longer: “Helmuth’s fine, he’s still growing,” Marc reported the following summer)[2], Helmuth taught himself enough Dutch to communicate with Heinrich Campendonk; chopped wood and built a fence; practiced painting and drawing, befriended Marc’s dog Russi; and demonstrated a talent for cooking and baking. This latter skill commanded Marc’s particular favor. Animated but sympathetic, Helmuth provided stability and encouragement. By Christmas Marc had breezily informed August that Helmuth would be staying on.[3]

As the calendar turned to 1911, the chrysalis of Sindelsdorf opened and released a new Marc to Munich. Seeking a sophisticated way to celebrate New Year’s, Helmuth pointed Marc toward a performance of Arnold Schönberg quartets. The music had a vivid impact on Marc, which he reported with great excitement to Maria, August, and a new friend who had missed the concert – Wassily Kandinsky. At a the soirée given by Marianne von Werefkin at which Marc and Kandinsky met at last in person, Helmuth was at Marc’s side, and witnessed the twinkle in the eye of fate that became Der Blaue Reiter.[4]

After the party, Helmuth and Franz took the late train from Munich to Penzburg, laughing and marveling over their adventure as they walked jauntily through the falling snow back to Sindelsdorf. Neither traveler was concerned for the future at that joyful moment, and mercifully, neither could know what the future held.

Helmuth Macke died in 1936 when his small boat capsized in a sudden storm on Lake Constance, having given his sailing companion the only life preserver.

[1] Franz Marc, August Macke: Briefwechsel. (Köln: DuMont, 1964), 20-21.

[2] Marc and Macke: Briefwechsel, 42.

[3] Marc and Macke: Briefwechsel, 28.

[4] Dominik Bartmann, Helmuth Macke, (Recklinghausen: Verlag Aurel Bongers, 1980), 26.

by Jean Marie Carey | 2 Dec 2013 | Art History

Lorna Simpson @ Haus der Kunst

One of the aspects of Lorna Simpson’s work I have always admired is the technical quality of her photographs. At her recent press conference at Haus der Kunst she confirmed what you’d expect from examining the gelatin prints in particular but really, upon close in-person inspection, her oeuvre: that Simpson develops, prints, mounts and even frames most of her photos by herself in a darkroom/studio in New York City.

This sort of mid-career retrospective represents more than 30 years of of photography, film, video, and drawing. Known (as in these photos have entered the canon) for her mid-1980s for her language driven large-scale works combining photographs and text, Simpson’s effective enigmas are clearly coded but spacious enough to still wonder about. One of the most interesting works on view in München are a series from the 1990s of large multi-panel photographs printed on felt, accompanied by text panels describing their locations and the intimate encounters that are described but only hinted at visually. At the edge of the Englischer Garten where something exactly as described is probably happening right now only not as well concealed, the effect was actually humane and tender as opposed to amusing. The exhibit, which unfortunately overlaps with some other very strong show and with Haus der Kunst’s interactive festival also showcases Simpson’s film and video works, a group of watercolors, and an archive of found photographs from the 1950s, which Simpson has embellished by creating replicas of, posing herself to mimic the originals.

by Jean Marie Carey | 20 Oct 2013 | Art History, German Expressionism / Modernism

I cannot explain better what 18 of the 21 photographs above are better than the Haus der Kunst press release about this very subject, so here it is, partially ellipsed for brevity:

Manfred Pernice ... will create an expansive, accessible installation consisting of various, often "recycled" works. The artist is interested not only in the reusing of found objects and materials of various origins, but also, what is more remarkable, he uses his own earlier works as architectural elements for new works or as installation pieces in altered contexts of meaning. Pernice's planned intervention for Haus der Kunst's central Middle Hall relates directly to the space's architecture and consists of two main elements: Pernice will place his architectural sculpture "Tutti" from the year 2010 in the middle of the room. A spiral staircase leads up to the sculpture's roof. From there, via a second staircase, the visitor reaches a bridge, which spans the Middle Hall and from which visitors can continually view the room from new perspectives. For the bridge, the artist will develop an installation, which, as a result of the work process, will evolve on site. This form of spontaneous response to the spatial conditions is characteristic of Pernice's sculptural approach.

My friend who came with me to the opening exclaimed more succintly: “Mager! Ich mochte lieber sehen…”

Additionally, the director of HdK, Okwui Enwezor (who is having a cusp birthday this week), described Pernice’s work as an “intervention in the global crisis of modernity.”

The artist and sponsors (the Friends of Haus der Kunst) also spoke at length about the sculptural installation, which seems to suggest they realize that even for HdK regular patrons it requires some type of backgrounding. I give HdK a lot of credit for trying out global-art-fair-type works in its austere central hall and for the integration (too seamlessly really) into the “renovation.”

Having just been in six airports in six days, the kind of indistinguishable elevations, chutes, and stopping spaces of those reminded me of Tutti IV in sort of a vague “I’m tired” (not “I’m aware of phenomenology) way. I think maybe also for people living in München the trappings of renovation – with both the Lenbachhaus and the Pinakothek der Moderne having recently reopened – plus the endless “installations” of scaffolding and rerouting at the Hauptbahnhof and Marienplatz – are part of the normal whirring scenic backdrop of the city.

by Jean Marie Carey | 1 Sep 2013 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism

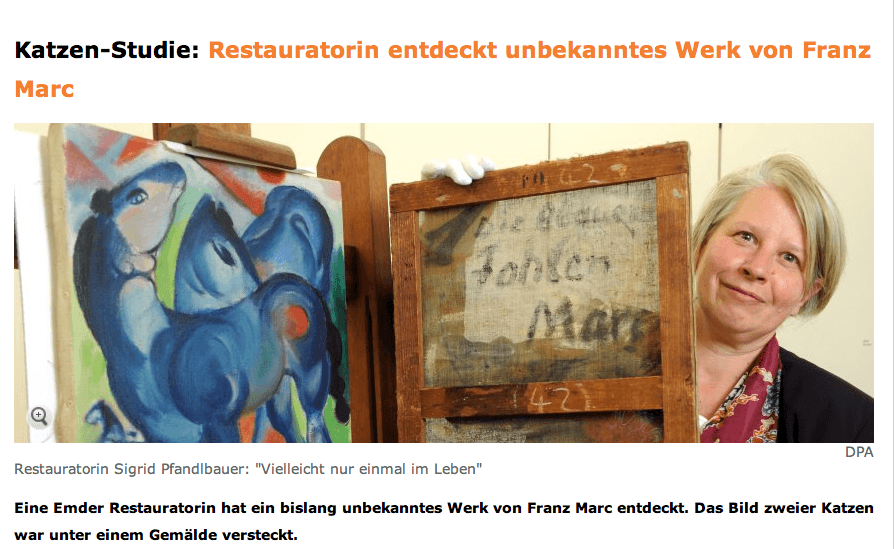

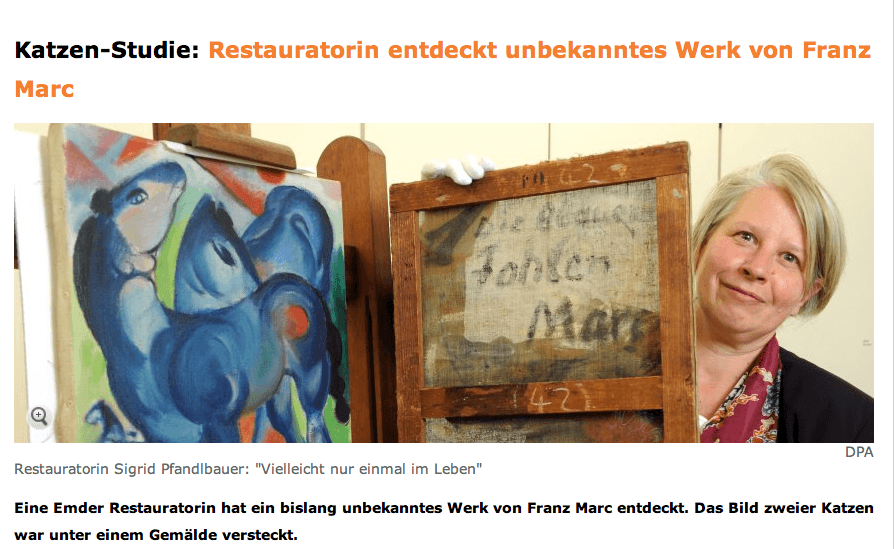

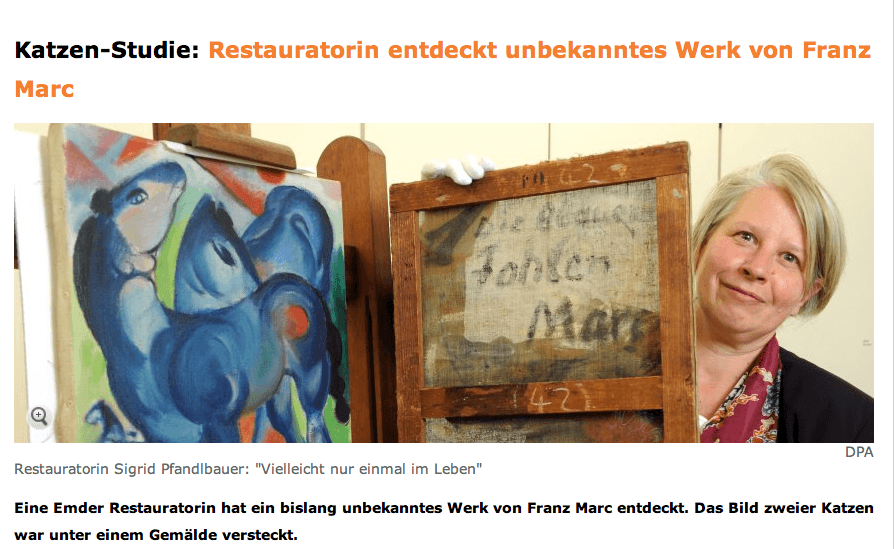

Der Spiegel online had a story today about an art restorer’s amazing discovery of a new Franz Marc painting on the reverse of 1913’s Blauen Fohlen. Sigrid Pfandlbauer of the Kunsthalle Emden found the study of two cats bearing Marc’s signature while restoring Blauen Fohlen for an upcoming exhibition. What an incredible, exciting discovery…how much there is still to be learned about Marc.

Der Spiegel online had a story today about an art restorer’s amazing discovery of a new Franz Marc painting on the reverse of 1913’s Blauen Fohlen. Sigrid Pfandlbauer of the Kunsthalle Emden found the study of two cats bearing Marc’s signature while restoring Blauen Fohlen for an upcoming exhibition. What an incredible, exciting discovery…how much there is still to be learned about Marc.