by Jean Marie Carey | 28 Jul 2016 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

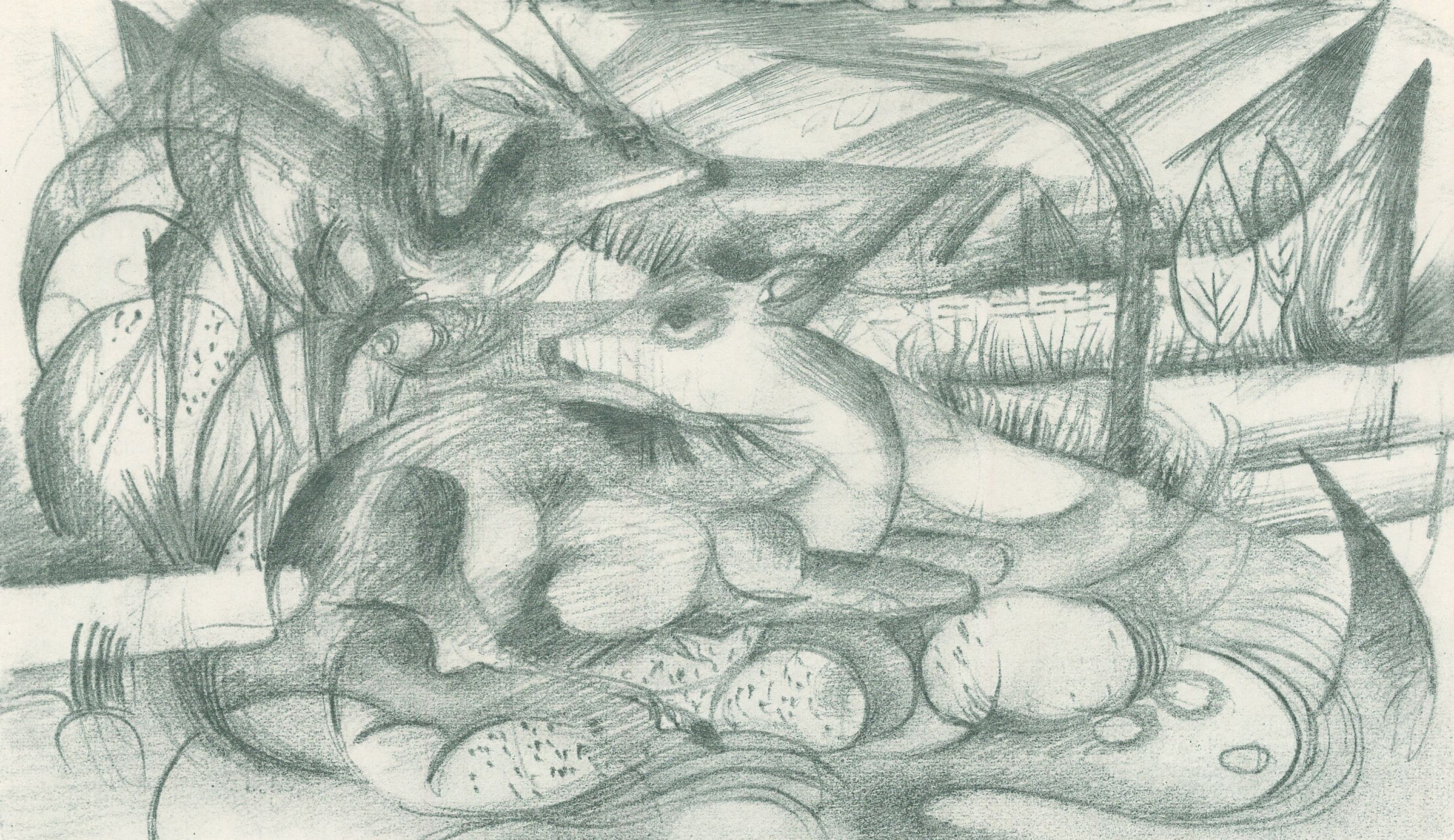

Franz Marc’s mysterious nude in a landscape from around 1911.

In clear contrast to the well-planned execution of the grazing horses on its front, the verso of Weidende Pferde IV is wild, mysterious, and haunting, and provides an intimate look at Franz Marc’s more intuitive approach to color and form.

Though the composition is partially obscured, the underlying motifs are clear enough.

Shown is a reclining female nude in a dimly lighted landscape under a deep blue sky. The figure rests on her back, her right leg is bent. Her head with long and flowing red hair is slightly tilted to the right; her arms clasped behind her. This figure is somewhat characteristic for Marc in terms of the visible hatching and decorated, colorful outlines. The left of the picture area seems to indicate another figure whose gender and position we can only guess at. The middle of the picture consists of a dramatic, deeply-hued landscape, which in turn is what the reclining nude in the foreground would be part of and also looking at. Though Marc often painted nude figures relaxing outside, this painting does not seem to correspond to another finished work.

Weidende Pferde IV, 1911

Weidende Pferde IV is also a stunning picture when considered in terms of Marc’s efforts to produce it: Three red horses with purple mane prance against a lemon-yellow sky and a deep blue rock formation. Marc had devoted a lot of time to developing the arrangement of the horses’ bodies in this formation. Marc had been preoccupied, and had made a difficult and lengthy process of, how exactly to balance the shapes and colors of the horses in the overall composition.

Weidende Pferde IV is the star of the second part of the exhibition trilogy “Franz Marc: Zwischen Utopie und Apokalypse,” presented by the Franz Marc Museum in Kochel on the 100th anniversary of the death year of the painter. This is one of just a few paintings that Marc saw hung in a museum himself, following its creation in 1911 and first display at the Thannhauser’s Galerie Moderne in Munich

The same year the collector Karl Ernst Osthaus purchased Weidende Pferde IV for the Folkwang Museum’s first incarnation in Hagen. The painting sold for 750 marks, as Marc triumphantly informed his brother Paul on 3 December 1911.

Marc had been constantly busy with live horses during his years in Kochel and Sindelsdorf (“Pferde auf Bergeshöh gegen die Luft stehend”), and he studied them in detail as he drew, printed and painted them.

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1909

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1910

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1910

The day before Alexej Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin and Adolf Erbslöh first visited Marc in Sindelsdorf on 3 February 1911, he wrote to Maria Marc who had at this time had left Bavaria to stay with her parents in Berlin, “Ich habe noch ein großes Bild mit 3 Pferden in der Landschaft, ganz farbig von einer Ecke zur anderen, angefangen, die Pferde im Dreieck aufgestellt. Die Farben sind schwer zu beschreiben. Im Terrain reiner Zinnober neben reinem Kadmium und Kobaltblau, tiefem Grün und Karminrot, die Pferde gelbbraun bis violett.”

The visitors loved the paintings, and by the day of his 31st birthday on 8 February Marc was a co-chairman of Neue Künstlervereinigung München.

Certainly the powerful painting of the reclining redhead should be regarded as an entirely discrete creation and given a proper name and place in the artist’s catalogue raisonné. It is curious that Harvard University’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, which purchased the painting when it was declared Entartete Kunst in 1937, has not taken the initiative to see that this is done. If only this painting could be permanently repatriated to Kochel, where it belongs.

by Jean Marie Carey | 12 Feb 2016 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

Franz Marc, Zwei Katzen, blau und gelb, 1912

The College Art Association conference was held 3-6 February in Washington, D.C., which for what I study is not a very interesting art city in the way New York City is…and D.C. is thus also very expensive to visit, since the trip doesn’t include a few precious hours in the Met, MoMA, Guggenheim, Neue Galerie, and so on.

If conferencing, not museum-visiting, is to be CAA’s focus going forward, the organization should do what the German Studies Association does, and move the meeting to some less-costly destinations that still have good mass transit and more of a range of hotel rooms, like Las Vegas or Atlanta.

This conference I had a lot of tasks I actually had to do, and one I wanted to do, or I should say was very curious about doing, attending the Historians of German, Scandinavian and Central European Art, or HGSCEA, [formerly just HGCEA, but, I guess the Munch people or something…] meeting, which this year took the form of a dinner honoring the long-reigning and undisputed chief Kandinsky scholar, Rose Carol Washton Long of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and Charles Haxthausen from Williams College.

I took the cryptic “honoring” on the invitation to mean “retiring,” which put me in mind of The King of the Cats. Miss Jessel’s “Haunted Palace” blog gives a nice account of the oral history tradition of this tale and its place in the folklore of the British Isles but, basically, without belaboring the point the outstanding extra-narrative moral for cat lovers and observers is probably that upon learning of the death of “the king of the cats,” all cats think that they are the designated heir to the throne.

So with respect to the fractious group of people who comprise known Kandinsky scholars…without an obvious heir apparent (to my mind there is not one, the once-promising regent having chosen their battles poorly), wouldn’t they all be prepared for anointment? As it turned out RCWL, in her very congenial speech, immediately made clear that while she was retiring from CUNY, she would not be relinquishing the reins to the Kandinsky dynasty anytime soon.

The “party” itself was quite a mysterious affair in that it did not appear as an “affiliated society” event anywhere on the CAA schedule (or the new Linked-In developer-sponsored) app, and was held in a small restaurant in Adams Morgan which was entirely closed except for the HSGCEA dinner. RSVP, affiliation, and credentials were thoroughly vetted at the door, and there were no nametags. Nametags would not have been much use anyway, since everyone went by a non-apparent nickname, like “Ricki” or “Mark.” And it was very dark inside the restaurant, Lillie’s (actual lighting shown), and you couldn’t see even across the room. So in other words it was pretty much how I expected it to be, except there wasn’t any kind of St. Bartholomew’s day type of fracas, duel, or mass feline exit through the fireplace.

The “party” itself was quite a mysterious affair in that it did not appear as an “affiliated society” event anywhere on the CAA schedule (or the new Linked-In developer-sponsored) app, and was held in a small restaurant in Adams Morgan which was entirely closed except for the HSGCEA dinner. RSVP, affiliation, and credentials were thoroughly vetted at the door, and there were no nametags. Nametags would not have been much use anyway, since everyone went by a non-apparent nickname, like “Ricki” or “Mark.” And it was very dark inside the restaurant, Lillie’s (actual lighting shown), and you couldn’t see even across the room. So in other words it was pretty much how I expected it to be, except there wasn’t any kind of St. Bartholomew’s day type of fracas, duel, or mass feline exit through the fireplace.

As to my own paper and panel, I was thrown off my presentating game a little – not a lot, or not as much as I had expected or was undoubtedly intended – and got a lot of good questions, including some very specific queries from some more-than-casual idolators about Animalisierung, of all things, about the painting Tierschicksale, and about what I had specifically set out to talk about, affect/effect disturbing/calming animal images have upon human animal/human-animal empathy.

Basically my claim is that disapprobation toward animal abusers – such as generated by the film The Cove and the work of Sue Coe – is not as strong a motivator as true identification with the animal subject. Hence the focus on Franz Marc. This isn’t necessarily as obvious an idea as it seems, and bears more discussion and exploration (which is why I am writing about it).

by Jean Marie Carey | 7 Jun 2015 | Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

Franz Marc, Skizzenbuch aus dem Felde, Skizze 24, 1915

I recently looked harder at Franz Marc’s experiments with poetry. I think you could say that much of Marc’s writing borrows structurally from poetry, and Marc read a lot of poetry, including all of the classics you’d expect, work by people he actually knew, such as Gottfried Benn and Else Lasker-Schüler. He was also interested in French Symbolist Stéphane Mallarmé, particularly Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard of 1897, having extensively annotated a copy of the text; contact with Hugo Ball, who was influenced by Mallarmé’s text/design, probably heightened Marc’s attention.

From 1912 Marc made doodles of lines of the following poem here and there, and of course the last line is what Marc had originally intended to be the title of the painting we know as Tierschicksale (1914). But it was not until 1915 he wrote these phrases down all together in his small portfolio of drawings made in Germany and France, during the war. It’s hard to say what the poem means, especially in the context of the (approximately – some leaves may be lost) 35-page sketchbook’s compact animal images, it is very interesting. A translation is elsewhere but here is the original poem:

“…ein rosafarbner Regen viel [sic] / auf grüne Wiesen. / die Luft war wie grünes Glas. / das Mädchen [sah auf’s] blickte ins Wasser; das Wasser war klar [rein] wie Kristall; da weinte das Mädchen. / die Bäume zeigten ihre Ringe; die Tiere ihre Adern”.

(Abgedruckt in: Klaus Lankheit: Franz Marc: sein Leben und seine Kunst. Köln: DuMont 1976, S. 124.)

by Jean Marie Carey | 6 Apr 2015 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, August Macke, Dogs!, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL

Hund vor der Welt, Franz Marc (1912). Oil on canvas, 118 by 83 centimetres, private collection, Switzerland

I write about this painting a lot – in fact I once, for quite a long time, devoted my academic research solely to this painting – but I realised I don’t often say anything about it in this space. So here is a little excerpt not from my current chapters but from a side project.

§ § §

Franz Marc made an innovative painting – a metaphysical genre portrait of his dog Russi – called Hund vor der Welt in the spring of 1912. The large vertical canvas shows the white hound seated on a hillside, facing the sun and the landscape at an angle across an indeterminate space. We have an account of what Marc had in mind in making this image in particular and Marc’s other thoughts about painting his frequent model.[1] There is also a substantial amount of documentation about Russi, the dog, who, as the artist’s constant companion, was a character who populated the art, photographs, and writing of other people. We even know where Russi was born, how he came as a puppy to live with Marc, and when he died.[2] So despite its slightly whimsical affect, Hund vor der Welt is an image of a real dog about whom much historical information is available. Marc made many paintings in which Russi also appears as a peripheral regular “character;” he leads the way in Im Regen (1912) and leaps after Die gelbe Kuh (1911).

August Macke, who came into frequent contact with Russi and made his own drawings of the dog, prevailed upon Marc to change the name of the painting from the one Marc originally had in mind, So wird mein Hund die Welt sieht.3 We know from Marc that he wanted to show Russi in thought, so the dog’s seated posture suggests that this is what is happening in the stillness. The strange view of the landscape Russi “sees” is nonetheless completely identifiable as a typical one from around Sindelsdorf where Marc lived. By placing buildings in the recognizable, managed farmlands of Bavaria, Marc suggests that people and animals are part of the same ecology, which, for dogs as the primary animal of domestication, is certainly true.

Russi did not have the life of a working dog, instead, with Marc, dividing his time between Munich, Berlin, and the small towns of Sindelsdorf and Ried. Russi lost part of his tail in 1911, an adjustment to his appearance that is reflected in his 1912 portrait. This shows that Marc had a commitment to showing morphologically accurate details even about the animals he painted, even as the paintings themselves broke with academic naturalism.

Die gelbe Kuh,

Franz Marc, 1911

189.2 × 140.52 cm

Oil on canvas

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. That is Russi Marc in the lower left corner.

[1] Franz Marc, Briefe, Schriften und Aufzeichnungen, (Leipzig: Kiepenheuer, 1989), 11. Observing Russi at this moment, Marc wonders: “Ich möchte mal wissen, was jetzt in dem Hund vorgeht.”

[2] Marc, Briefe, 196-197.

[3] Franz Marc, August Macke, Briefwechsel, (Köln: DuMont, 1964), 124-126.

by Jean Marie Carey | 5 Mar 2015 | August Macke, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

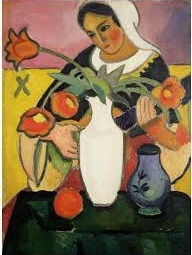

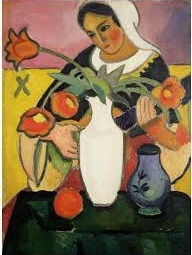

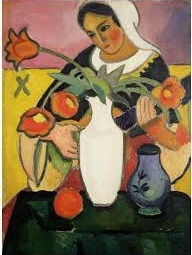

Die Lautenspielerin, August Macke, 1910

“Recent publications” is in quotes because all of the great opportunities to preach the gospel of Marc lately have come to me strictly through the generosity of other people, so I will quickly get to the point of thanking Trang Vu Thuy and the curatorial staff at the Lenbachhaus and Janine Arnold of Notes About Art. (Please click through the links to view the articles themselves.)

My post (which is present entirely owing to the patience of Vu Thuy) “Ein Manifest der Freundschaft” is in honor of the August Macke und Franz Marc: Eine Künstlerfreundschaft exhibition (on through 3 May 2015 in the Lenbachhaus Kunstbau) and concerns one of my favorite subjects, the Paradies mural.

“Von »Köstlichen Figürchen« und »Wunderherlichen Farben«” by assistant curator Monika Bayer-Wermuth is actually the most wonderful post, though, on the gifts sent by the Marcs to the Mackes and is told in the same thoughtful, personal vein as are many of the chapters in the companion catalogue.

Thanks to the generous invitation of Arnold, I have two entries on her Notes About Art website, one called “Confrontations & Reconciliations” about my interpretation of Franz Marc’s gift of the painting Blaues Pferdchen, Kinderbild to August Macke and the other a bit about the history of Marc’s two Turm der blauen Pferde.

I am very happy to see art historians collaborating across distance and language just because we like the art and want for other people to be able to know about and appreciate the work of Der Blaue Reiter. (more…)