The Wilhelmine Insurgency

The Wilhelmine Insurgency

Franz Marc’s metaphysical visions were never far from him, occurring in “Two Paintings” in the confident statement, “What appears spectral today will be natural tomorrow.”[1] This sentence is in several respects characteristic not only of Marc but of that short period in European thought that runs from 1902 to 1914. It was the period in which Henri Bergson’s élan vital, and philosophical ideas about the confusion of immediate subjective experience, uncategorized and uncategorizable, became commonplace. As was the case with Wilhelm Worringer’s concepts, this discussion spread quickly into artistic and literary circles especially in France and in England but also in Germany. The rejection of scientific optimism touched a nerve. At the beginning of the 20th Century this was a mood that had been encouraged by the rapid introduction of new styles in painting, sculpture, and the applied arts that had accompanied each of the recent splits in the German art world, with one “Secession” leading to another, and with the “advanced” artists of one decade often becoming the reactionaries of the next. Throughout the 19th Century — especially in France — artists had been rebelling against the established academies and official salons and had looked for new ways of showing their work in rival salons des refusés.

In Germany by the end of the 1800s the situation had become dramatic. Many writers wondered about what was “German.” In the art world the question arose especially from the fact that, as Robin Lenman pointed out in an article preceding his book, Artists and Society in Germany, 1850-1914 (1997)[2], state and municipal patronage of the arts in Germany was on a particularly large scale, so that the relation of art to the state became of central importance for artists trying to make a living. Those artists who were not included, or who thought themselves inadequately represented in the large official exhibitions held in the major German cities, had economic as well as aesthetic reasons for creating new outlets for their work. As the painter Lovis Corinth remarked on joining the Munich Secession in 1892, “I had the instinctive sense that I could get ahead in this clique.”[3]

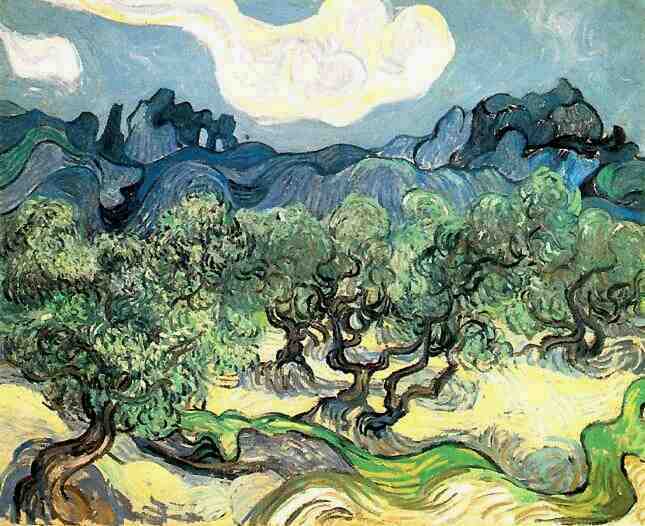

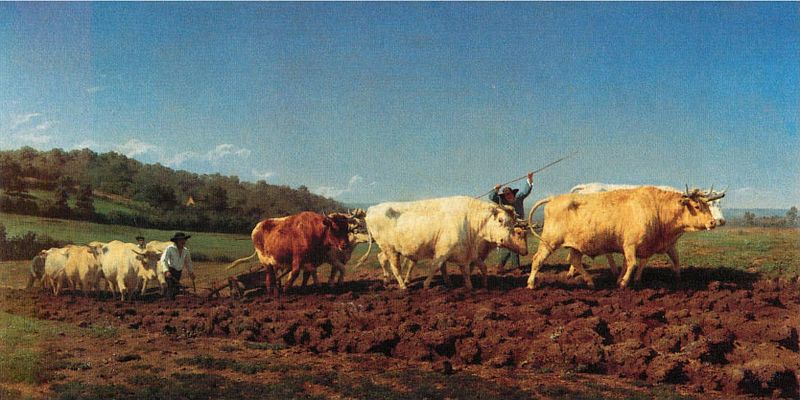

The first of these Secessions was that in Munich in 1892, the subject of a study by Maria Makela,[4] following to some extent the model of Peter Paret’s pioneering book of 1980 on the Berlin Secession. Similar movements were started in other German cities, for example Düsseldorf and Dresden. In Austria the Vienna Secession was founded in 1897.[5] Each of these movements had its own emphasis, but artists moved from one city to another. Many Munich artists went to Berlin at a time when the imperial capital seemed a richer and more dynamic place than Munich. In each center it had been the controversy over the showing of “foreign” art that had been one of the principal issues over which the split took place. The Munich Secession began by emphasizing naturalism in opposition to the sentimental scenes of Bavarian peasant life popular among local painters and patrons, but it too was protesting against the elaborate grandiose state portraits and history paintings of Franz von Lenbach and Anton von Werner, the director of the School of Fine Arts in Berlin.

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century it was Munich that was the artistic capital of Germany. The collections that King Ludwig I had assembled before 1848 and the neoclassical buildings that housed them, the number of artists living and working in the city (some 9,000 by 1894, rising to 14,000 in 1907), the possibilities of café life — all made the Bavarian capital an attractive place for artists, both from inside Germany and elsewhere, as well as writers, visiting connoisseurs, and tourists. Bavaria retained a strong sense of character and traditions. The inhabitants of Munich were very conscious of the advantages to their city of its reputation as a center of artistic life. One of the issues that had led to the founding of the Secession was the invitation to international artists to send work to the annual exhibitions, though even among Secession members there was soon a movement to limit the number of such works shown: in 1893 more than half the exhibitors were foreign; as a result of complaints by Munich artists the number had fallen to 17 percent by 1908.[6]

The applied arts showed even more clearly than the work of the painters how diffuse and contradictory the modern movement had become.[7] Indeed one of the characteristics of “advanced” art in Germany at the beginning of the century was, as Seth Taylor points out in his study of the influence of Nietzsche on certain aspects of Expressionist literature, Left-Wing Nietzscheans, the tension between the artist’s desire to become socially involved in the problems of an increasingly urbanized, society and the equally strong desire to withdraw from the world into a rural Arcadia was never really resolved: “The longing for social involvement was contradicted by a libertarian desire to withdraw from society completely.” [8]

One of the new artists in Munich made quite clear what he thought of the Secession’s exhibition in 1902:

Hanging on the walls, it seems, are the “same old things” we saw long ago, only somewhat faded — pictures that take as their point of departure the literal repetition of nature and thus forfeit the luster of the artist’s intentions.

The writer was Kandinsky. Many of Marc’s and Kandinsky’s works and other important collections and donations are now housed, ironically, in the mansion that belonged to Franz von Lenbach, the wealthy painter of official portraits and one of the main figures against whom Kandinsky was reacting. A study by the gallery’s then-director, Armin Zweite, with biographies of the artists and commentaries by Annegret Hoberg on the paintings reproduced, The Blue Rider in the Lenbachhaus, Munich (2000) provides an indication of the riches of the collection which also includes works by Münter, Macke, Alexei Jawlensky, and Paul Klee.

Marc provided a link between Munich and Berlin and between the Blaue Reiter and the very different artists of the Brücke and the circle around the Berlin dealer and critic Herwarth Walden’s literary and artistic weekly, Der Sturm. Marc collaborated with Walden to organize the Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon in Berlin in 1913. There, too, Marc met Walden’s former wife, the poet Else Lasker-Schüler. This relationship produced Marc’s Postcards to Prince Jussuf. The originals of these twenty-eight small paintings, all featuring animals, sent by Marc to Lasker-Schüler between 1912 and 1914, are now divided between the Bavarian state collections and the Nationalgalerie in Berlin and are reproduced together in a book by Peter-Klaus Schuster, which tells in a preface much about this collaborative project.[9]

The Symbolists at the end of the 19th Century had been concerned with “the Spiritual.” In France this had involved some of them with the Rosicrucian revival of the 1890s, and the Symbolist heritage left a strong imprint on Munich painters and writers, among them the criminally undertranslated poet Stefan George. They were interested in the new spiritualist movements, especially Theosophy, whose apostle Rudolf Steiner was read by Kandinsky. The Russians in Munich brought with them their own tradition of mystical speculation.[10]

[1] Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, The Blaue Reiter Almanac, 104.

[2] “Painters, Patronage and the Art Market in Germany, 1880-1914,” Past and Present, No. 123, May 1989.

[3] Peter Paret, The Berlin Secession: Modernism and Its Enemies in Imperial Germany, (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1980) 269.

[4] Maria Martha Makela, The Munich Secession: Art and Artists in Turn-of-the-Century Munich, (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1990).

[5] Carl Schorske, Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture (Knopf, 1980), 200-209.

[6] For a valuable detailed account of the economic situation of Munich artists, see Robin Lenman, “A Community in Transition: Painters in Munich 1886–1924,” in Central European History Vol. 10, March 1983. See also his “Politics and Culture: The State and the Avant-Grade in Munich, 1886–1914” in Richard Evans, ed., Society and Politics in Wilhelmine Germany (Barnes and Noble, 1978).

[7] The monograph by Annelies Krekel-Aalberse, Art Nouveau and Art Deco Silver (1989), illustrates the tension in trends, and also shows, in such objects as a silver caviar dish or a tea caddy set with amethysts, the class for whom artisans were working.

[8] Seth Taylor, Left-Wing Nietzscheans: The Politics of German Expressionism 1910–1920 (Walter de Gruyter, 1990).

[9] Peter-Klaus Schuster, Franz Marc, and Else Lasker-Schüler, Franz Marc, postcards to Prince Jussuf, (Munich: Prestel, 1988).

[10] For a discussion of these see Rose-Carol Washton Long, Kandinsky: The Development of an Abstract Style (Oxford University Press,1980), especially Chapter 2.