by Jean Marie Carey | 12 Feb 2016 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

Franz Marc, Zwei Katzen, blau und gelb, 1912

The College Art Association conference was held 3-6 February in Washington, D.C., which for what I study is not a very interesting art city in the way New York City is…and D.C. is thus also very expensive to visit, since the trip doesn’t include a few precious hours in the Met, MoMA, Guggenheim, Neue Galerie, and so on.

If conferencing, not museum-visiting, is to be CAA’s focus going forward, the organization should do what the German Studies Association does, and move the meeting to some less-costly destinations that still have good mass transit and more of a range of hotel rooms, like Las Vegas or Atlanta.

This conference I had a lot of tasks I actually had to do, and one I wanted to do, or I should say was very curious about doing, attending the Historians of German, Scandinavian and Central European Art, or HGSCEA, [formerly just HGCEA, but, I guess the Munch people or something…] meeting, which this year took the form of a dinner honoring the long-reigning and undisputed chief Kandinsky scholar, Rose Carol Washton Long of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and Charles Haxthausen from Williams College.

I took the cryptic “honoring” on the invitation to mean “retiring,” which put me in mind of The King of the Cats. Miss Jessel’s “Haunted Palace” blog gives a nice account of the oral history tradition of this tale and its place in the folklore of the British Isles but, basically, without belaboring the point the outstanding extra-narrative moral for cat lovers and observers is probably that upon learning of the death of “the king of the cats,” all cats think that they are the designated heir to the throne.

So with respect to the fractious group of people who comprise known Kandinsky scholars…without an obvious heir apparent (to my mind there is not one, the once-promising regent having chosen their battles poorly), wouldn’t they all be prepared for anointment? As it turned out RCWL, in her very congenial speech, immediately made clear that while she was retiring from CUNY, she would not be relinquishing the reins to the Kandinsky dynasty anytime soon.

The “party” itself was quite a mysterious affair in that it did not appear as an “affiliated society” event anywhere on the CAA schedule (or the new Linked-In developer-sponsored) app, and was held in a small restaurant in Adams Morgan which was entirely closed except for the HSGCEA dinner. RSVP, affiliation, and credentials were thoroughly vetted at the door, and there were no nametags. Nametags would not have been much use anyway, since everyone went by a non-apparent nickname, like “Ricki” or “Mark.” And it was very dark inside the restaurant, Lillie’s (actual lighting shown), and you couldn’t see even across the room. So in other words it was pretty much how I expected it to be, except there wasn’t any kind of St. Bartholomew’s day type of fracas, duel, or mass feline exit through the fireplace.

The “party” itself was quite a mysterious affair in that it did not appear as an “affiliated society” event anywhere on the CAA schedule (or the new Linked-In developer-sponsored) app, and was held in a small restaurant in Adams Morgan which was entirely closed except for the HSGCEA dinner. RSVP, affiliation, and credentials were thoroughly vetted at the door, and there were no nametags. Nametags would not have been much use anyway, since everyone went by a non-apparent nickname, like “Ricki” or “Mark.” And it was very dark inside the restaurant, Lillie’s (actual lighting shown), and you couldn’t see even across the room. So in other words it was pretty much how I expected it to be, except there wasn’t any kind of St. Bartholomew’s day type of fracas, duel, or mass feline exit through the fireplace.

As to my own paper and panel, I was thrown off my presentating game a little – not a lot, or not as much as I had expected or was undoubtedly intended – and got a lot of good questions, including some very specific queries from some more-than-casual idolators about Animalisierung, of all things, about the painting Tierschicksale, and about what I had specifically set out to talk about, affect/effect disturbing/calming animal images have upon human animal/human-animal empathy.

Basically my claim is that disapprobation toward animal abusers – such as generated by the film The Cove and the work of Sue Coe – is not as strong a motivator as true identification with the animal subject. Hence the focus on Franz Marc. This isn’t necessarily as obvious an idea as it seems, and bears more discussion and exploration (which is why I am writing about it).

by Jean Marie Carey | 24 Nov 2015 | Art History, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

Miranda, 1914

So I am pleased and grateful to report the publication of my first peer-reviewed anthology chapter in the journal Expressionismus in the special issue Der performative Expressionismus. The article is called “‘Der Sturm’ und die Wilden.? Franz Marcs Entscheidungskampf mit der Theatralität,” which translates imperfectly to something like “‘The Tempest’ and the Savages: Franz Marc’s Decisive Encounter with Theatricality.” (Entscheidungskampf can also mean something like Armageddon/scorched earth, which in this case is accurate.)

The article is currently behind the Neofelis Verlag paywall (for a very reasonable €13), but you will soon find it on JSTOR and elsewhere. If you have any questions about how to view article please email me.

This side project to my main research corrects some chronological errors that have consistently been repeated in both Expressionist and Dada literature about the collaboration of Franz Marc and Hugo Ball on a planned production of The Tempest at the Münchner Kammerspiele. Because the story takes place in early 1914, it has been tempting for scholars – some of them quite formidable – to conclude that it was the war that usurped these plans. However, that is not at all the case.

“What really happened” is of course quite interesting on its face and as a reminder that we in fact know very little in the way of actual facts about the historical avant-gardes, who are fast disappearing into hagiography.

More interesting to me, in terms of writing and research, was the analysis of the two small drawings Marc made as character studies of The Tempest’s Miranda and Caliban personalities. This is the first time these drawings, housed in the Kunsthalle Basel, have been subjected to such scholarly scrutiny and each contains many clues and psychological implications.

I was also intrigued to discover that Marc had sent a draft of his June 1914 essay »Das abstrakte Theater,« (also analyzed in the article) about his frustrating foray into the theater to August Macke, and that the two had previously had many exchanges about the performing arts. In fact it is clear that the very precocious Macke – who at only 21 had been the chief set designer for the theater in Düsseldorf – had had a great influence on Marc’s ideas on the subject – ideas being the key word, since Marc had no firsthand dramaturgical knowledge up until this point.

My colleague here at the university, Prof. Dr. August Obermayer, was the very gracious translator but he also provided invaluable editing and advising, and the Neofelis editors were also a pleasure to learn from.

All in all a great experience and I hope readers will find the unraveling of Expressionist mysteries as fascinating as I do.

Caliban, 1914

by Jean Marie Carey | 21 Jan 2015 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, August Macke, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Helmuth Macke, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

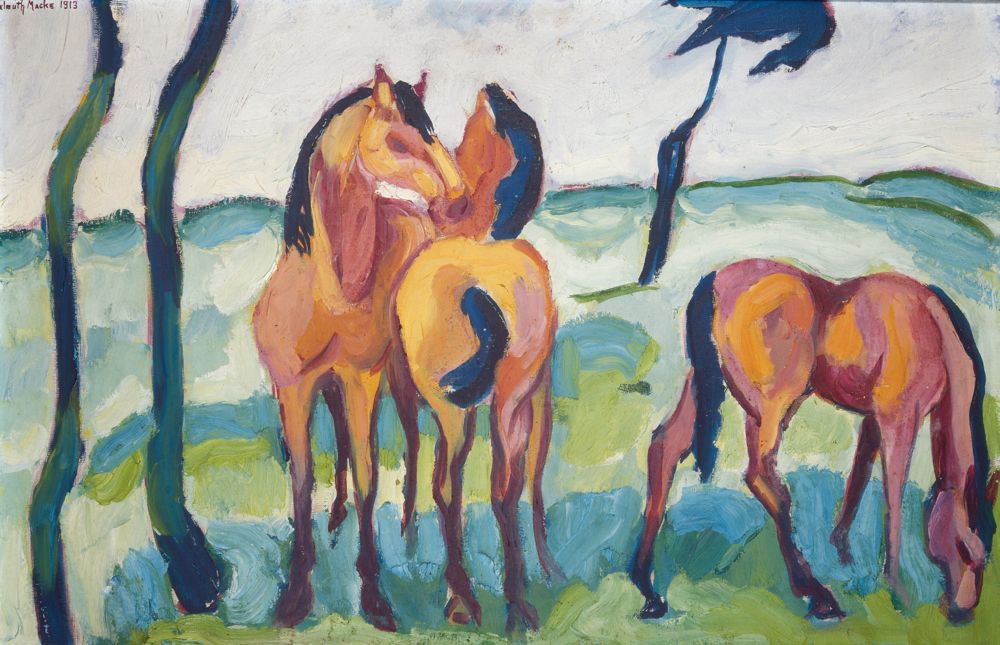

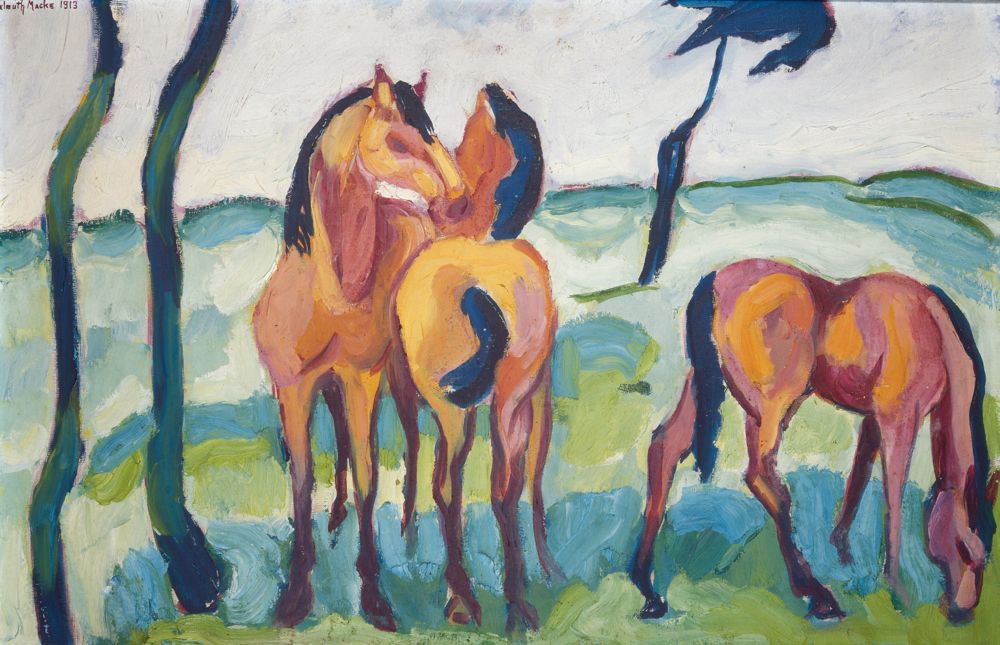

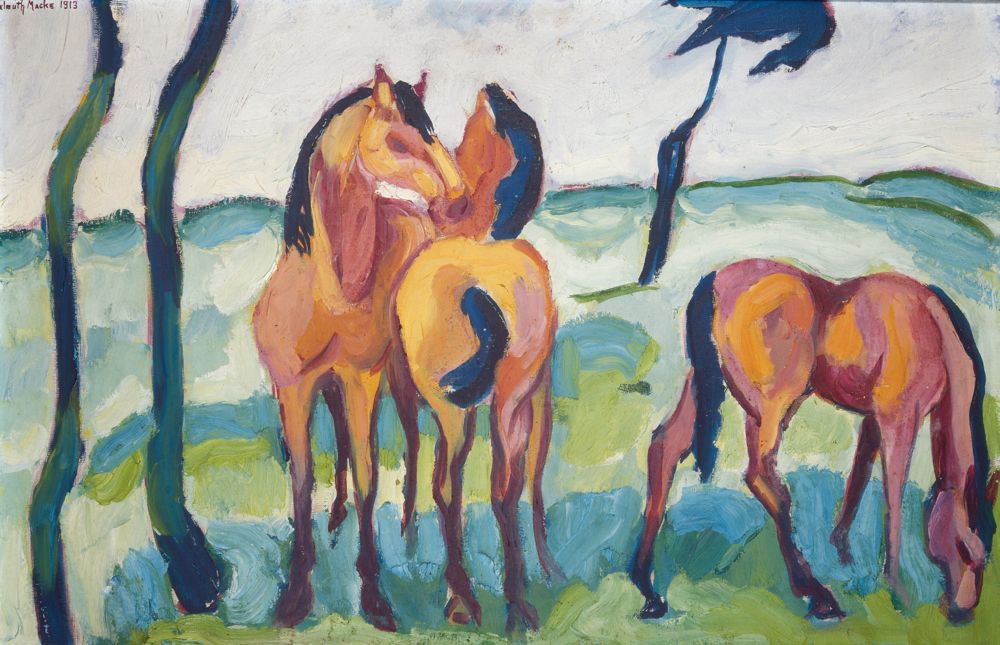

Helmuth Macke,

Drei Pferde,

1913

“The ‘boarding school’ is in session,” Franz Marc wrote nervously to his friend August Macke.[1] Pining for company in the same letter, Marc nonetheless wondered if August should come and get Helmuth Macke, August’s young cousin, whom the Macke family had deposited some weeks earlier at Marc’s small apartment in rural Sindelsdorf. It was late November 1910. Marc would soon turn 31, and Helmuth was 18. Until Helmuth’s arrival, Marc had been working alone for some time. At the insistence of her concerned parents, Maria Marc had returned to Berlin. Marc was just beginning to see the slightest of incomes from his painting, but he was irritable and distracted. And now August, himself adjusting with his wife Elisabeth to the birth of their son, expected Marc to find ways to entertain a teenager.

Yet Helmuth was resourceful and clever. During the weeks in Sindelsdorf, (which become months and longer: “Helmuth’s fine, he’s still growing,” Marc reported the following summer)[2], Helmuth taught himself enough Dutch to communicate with Heinrich Campendonk; chopped wood and built a fence; practiced painting and drawing, befriended Marc’s dog Russi; and demonstrated a talent for cooking and baking. This latter skill commanded Marc’s particular favor. Animated but sympathetic, Helmuth provided stability and encouragement. By Christmas Marc had breezily informed August that Helmuth would be staying on.[3]

As the calendar turned to 1911, the chrysalis of Sindelsdorf opened and released a new Marc to Munich. Seeking a sophisticated way to celebrate New Year’s, Helmuth pointed Marc toward a performance of Arnold Schönberg quartets. The music had a vivid impact on Marc, which he reported with great excitement to Maria, August, and a new friend who had missed the concert – Wassily Kandinsky. At a the soirée given by Marianne von Werefkin at which Marc and Kandinsky met at last in person, Helmuth was at Marc’s side, and witnessed the twinkle in the eye of fate that became Der Blaue Reiter.[4]

After the party, Helmuth and Franz took the late train from Munich to Penzburg, laughing and marveling over their adventure as they walked jauntily through the falling snow back to Sindelsdorf. Neither traveler was concerned for the future at that joyful moment, and mercifully, neither could know what the future held.

Helmuth Macke died in 1936 when his small boat capsized in a sudden storm on Lake Constance, having given his sailing companion the only life preserver.

[1] Franz Marc, August Macke: Briefwechsel. (Köln: DuMont, 1964), 20-21.

[2] Marc and Macke: Briefwechsel, 42.

[3] Marc and Macke: Briefwechsel, 28.

[4] Dominik Bartmann, Helmuth Macke, (Recklinghausen: Verlag Aurel Bongers, 1980), 26.

by Jean Marie Carey | 15 Dec 2014 | Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism

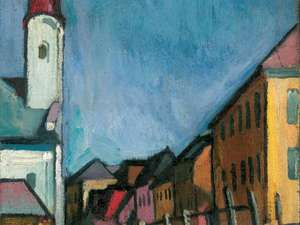

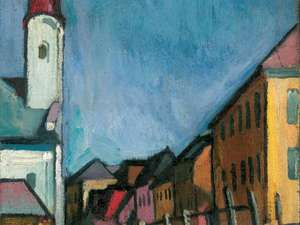

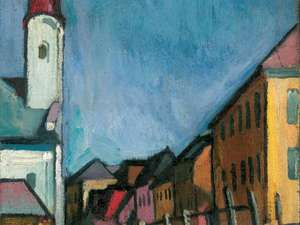

Is this colorful village scene painted by August Macke?

I have been working on a project about authenticating a painting maybe misattributed to one of my Expressionist painters (yet maybe made by another), so I was very interested to see a story crop up over the weekend in the Münchner Merkur online edition (pretty sure Süddeutsche Zeitung, usually so on top of all news Bayern, must be spitting nails!) about a man who thinks he owns a painting by August Macke.

Even more intriguingly, the painting would have been made in 1910, the year Macke spent in Tegernsee during which time Franz Marc often came to visit the Macke family, sometimes walking there through Oberbayern from Sindelsdorf to Tegernsee with Russi Marc. This period of time is recounted with warmth and in detail by Margarethe Jochimsen and Peter Dering in the book August Macke in Tegernsee.

The man who owns the painting, Herbert Spiess, claims to have purchased it from an art dealer in Vienna in 1984. Spiess told the Merkur he became convinced the painting, a small streetscape, was a Macke simply through visual association. (The Westfälische Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte in Münster says “no” in the Merkur’s story; no comment from the Lenbachhaus or the August Macke Haus in Bonn).

Macke enjoyed his time in Tegernsee. This was a happy year for Macke and his wife, Elizabeth and their first son, Walter, was born in the quiet lakeside village. Macke was more or less amused by his botany-obsessed landlords, whose Bayerische dialect he was able to penetrate with Marc’s help. Stubbornly autodidactic and much more fanciful and imaginative than he appeared at a glance, Macke spent hours doing “copying exercises” with Marc (and doing some other fun stuff too), and experimented with many styles of painting and drawing in 1910.

During this time, despite being in a very attractive location, Macke concentrated on portraiture, making many sketches and paintings of Walter, Elizabeth, and the famous portrait of Marc.

Bildnis Franz Marc, August Macke, 1910

But Macke also was always making all sorts of things, from tapestries to fabric designs to theater decorations. So it’s certainly possible this single painting is something he just knocked out during this period of great productivity – Macke was exceedingly prolific and made more than 200 paintings between 1909 and late 1910, when the young family returned to Bonn, leaving cousin Helmuth Macke to stay with Marc.

So it’s hard to say, from looking alone, if this painting could be Macke’s. I hope it is but (and this is really just a very strong intuition as much as empirical assessment) my feeling is that it might not be. To my eye the painting lacks that little flourish of passion and verve, and of capturing the “inner realities” of the beauty he was in the physical world, that is the beautiful Expressionist hallmark of Macke’s oeuvre. With any luck I’m wrong though, and the world will have a new August Macke painting to admire.

Anyway, the reporter, Vera Markert, asks that if you have any information or ideas about the painting to get in touch with the Merkur via email at kultur@miesbacher-merkur.de wenden.

by Jean Marie Carey | 28 Jul 2014 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL

Brigita Hofer cleans, fills, patches, and recolors “Paradies.”

Here is a short article on the ruhr.de website about the restoration of the Paradies mural made by Franz Marc and August Macke in 1912 at the Mackes’ home in Bonn. It’s an interesting little piece and the website also has some photographs of the movement of the mural, in the 1980s, from its original location to the Museum für Kunst ind Kultur/Westfälisches Landesmuseum in Münster, where it lives today (there is a pretty nice replica at the August Macke Haus though). Like a lot of people I am sad that the museums can’t just switch the murals back, but this article sort of explains why that will not happen.

The restorer, Brigita Hofer, has discovered that the mural is pretty structurally unsound, giving it a soundness rating (as happens with earthquake-damaged buildings as I recently learned) of around 25, which means there’s a better than one in four chance it could collapse under any further stress. Hofer has been filling in surface cracks and erosions with non-expanding plaster and emulsifier with the tiniest of syringes. Hofer also restored some of the mural’s damaged or faded paint. In doing so she discovered that Macke and Marc had made a lot of adjustments to the mural as they worked together, repainting Eve’s face and the deer. Hofer also learned from a heretofore covered note that Maria Marc had painted the wasp at the bottom of the mural.

I am fascinated with this mural, as you might guess from how often I write about it, not for the least reason that it seems to be a truly collaborative effort that resulted in a distinct “style” that is identifiably that of both painters but is also a unique meshing of their ideas and talents. Even the animals don’t look exactly like Marc’s other animals, and for both, the palette is a bit subdued. (Except Adam reaching to embrace the monkey on the top left branch though and turning from the other figures – I think that’s a Marc thing. There is a large image of the mural in the post just before this one.)

The “party” itself was quite a mysterious affair in that it did not appear as an “affiliated society” event anywhere on the CAA schedule (or the new Linked-In developer-sponsored) app, and was held in a small restaurant in Adams Morgan which was entirely closed except for the HSGCEA dinner. RSVP, affiliation, and credentials were thoroughly vetted at the door, and there were no nametags. Nametags would not have been much use anyway, since everyone went by a non-apparent nickname, like “Ricki” or “Mark.” And it was very dark inside the restaurant, Lillie’s (actual lighting shown), and you couldn’t see even across the room. So in other words it was pretty much how I expected it to be, except there wasn’t any kind of St. Bartholomew’s day type of fracas, duel, or mass feline exit through the fireplace.

The “party” itself was quite a mysterious affair in that it did not appear as an “affiliated society” event anywhere on the CAA schedule (or the new Linked-In developer-sponsored) app, and was held in a small restaurant in Adams Morgan which was entirely closed except for the HSGCEA dinner. RSVP, affiliation, and credentials were thoroughly vetted at the door, and there were no nametags. Nametags would not have been much use anyway, since everyone went by a non-apparent nickname, like “Ricki” or “Mark.” And it was very dark inside the restaurant, Lillie’s (actual lighting shown), and you couldn’t see even across the room. So in other words it was pretty much how I expected it to be, except there wasn’t any kind of St. Bartholomew’s day type of fracas, duel, or mass feline exit through the fireplace.