by Jean Marie Carey | 7 Jun 2015 | Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

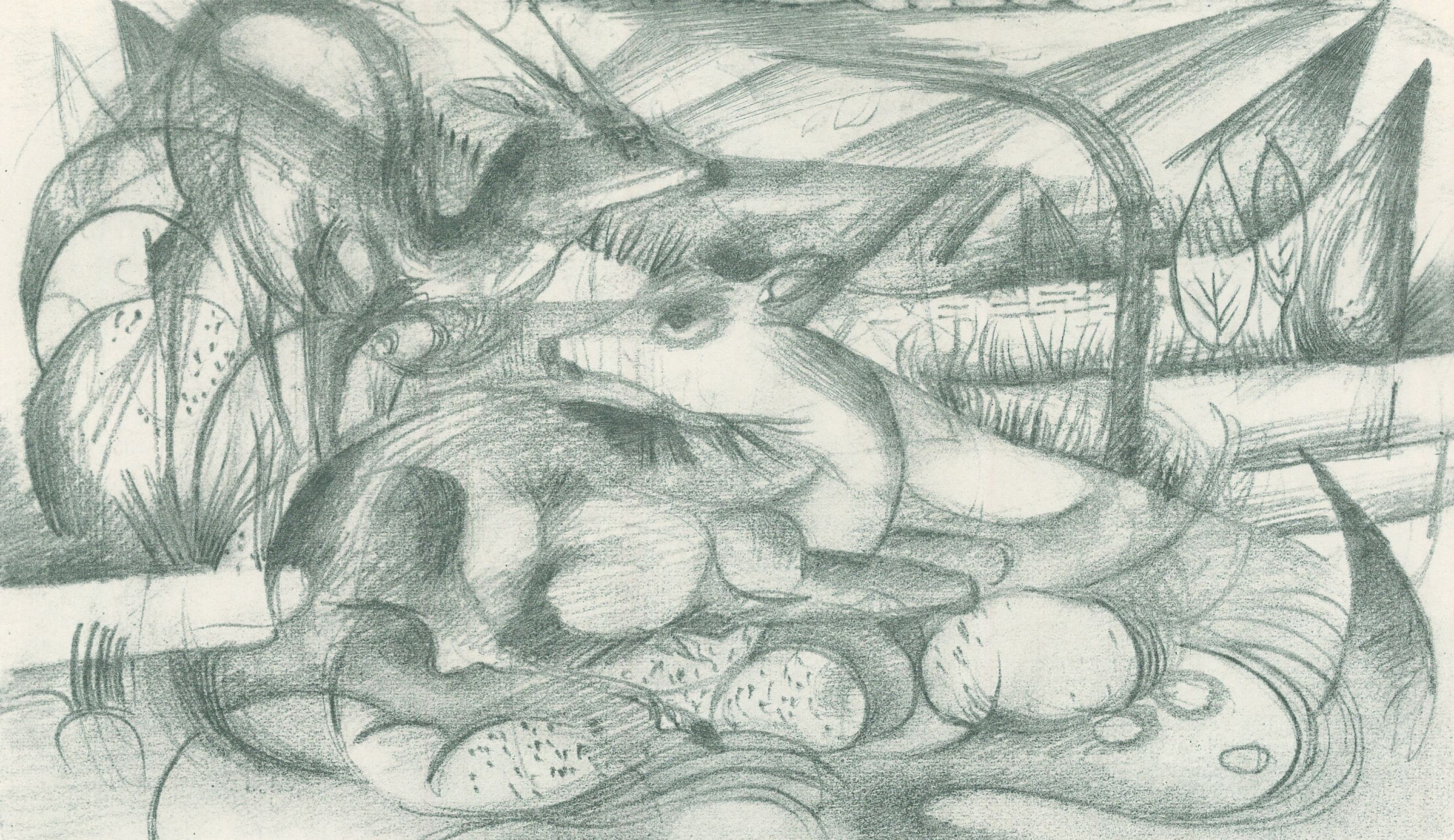

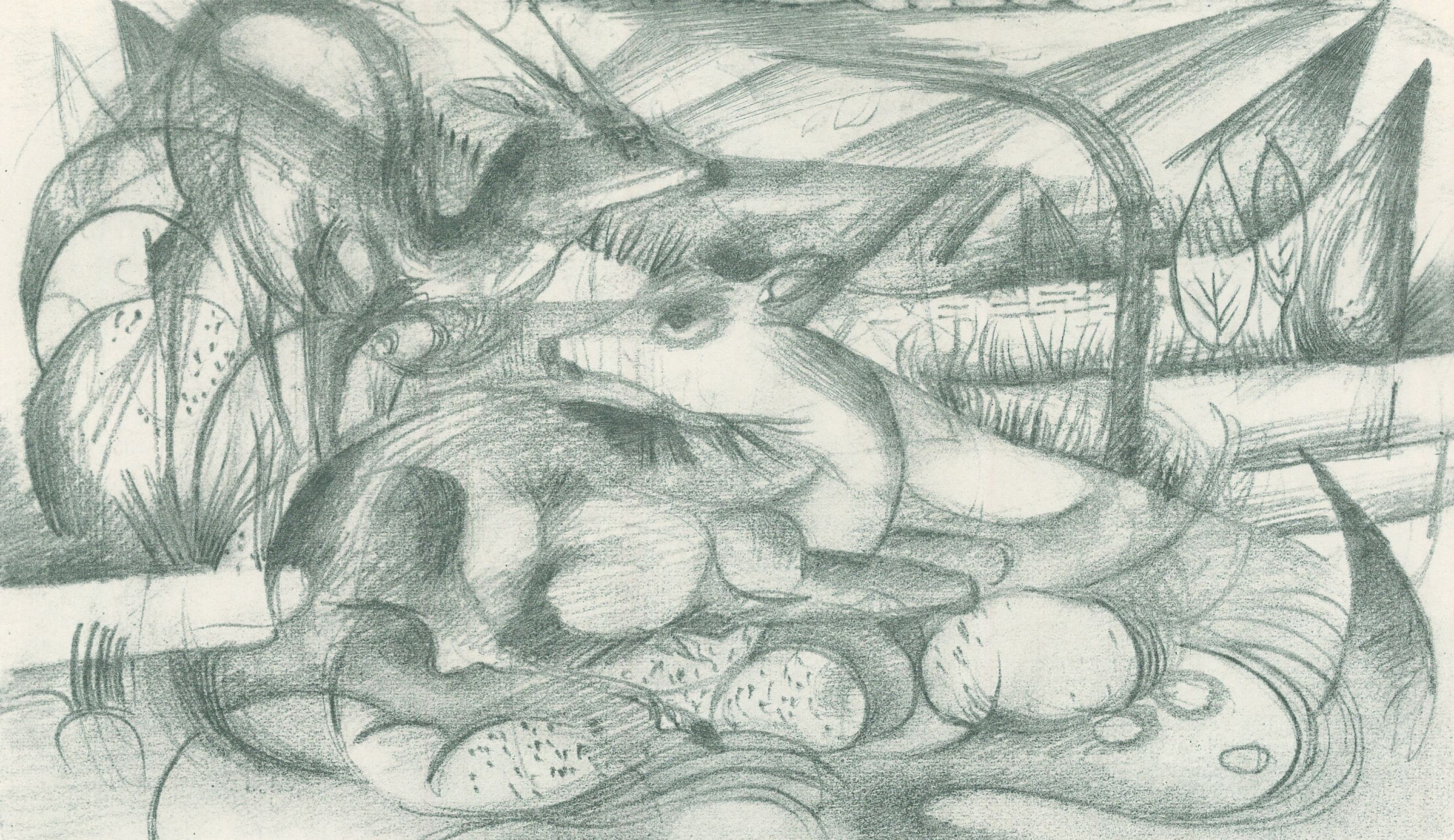

Franz Marc, Skizzenbuch aus dem Felde, Skizze 24, 1915

I recently looked harder at Franz Marc’s experiments with poetry. I think you could say that much of Marc’s writing borrows structurally from poetry, and Marc read a lot of poetry, including all of the classics you’d expect, work by people he actually knew, such as Gottfried Benn and Else Lasker-Schüler. He was also interested in French Symbolist Stéphane Mallarmé, particularly Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard of 1897, having extensively annotated a copy of the text; contact with Hugo Ball, who was influenced by Mallarmé’s text/design, probably heightened Marc’s attention.

From 1912 Marc made doodles of lines of the following poem here and there, and of course the last line is what Marc had originally intended to be the title of the painting we know as Tierschicksale (1914). But it was not until 1915 he wrote these phrases down all together in his small portfolio of drawings made in Germany and France, during the war. It’s hard to say what the poem means, especially in the context of the (approximately – some leaves may be lost) 35-page sketchbook’s compact animal images, it is very interesting. A translation is elsewhere but here is the original poem:

“…ein rosafarbner Regen viel [sic] / auf grüne Wiesen. / die Luft war wie grünes Glas. / das Mädchen [sah auf’s] blickte ins Wasser; das Wasser war klar [rein] wie Kristall; da weinte das Mädchen. / die Bäume zeigten ihre Ringe; die Tiere ihre Adern”.

(Abgedruckt in: Klaus Lankheit: Franz Marc: sein Leben und seine Kunst. Köln: DuMont 1976, S. 124.)

by Jean Marie Carey | 5 Mar 2015 | August Macke, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

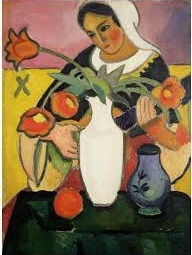

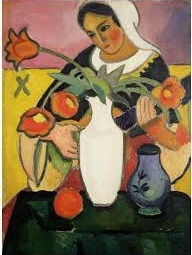

Die Lautenspielerin, August Macke, 1910

“Recent publications” is in quotes because all of the great opportunities to preach the gospel of Marc lately have come to me strictly through the generosity of other people, so I will quickly get to the point of thanking Trang Vu Thuy and the curatorial staff at the Lenbachhaus and Janine Arnold of Notes About Art. (Please click through the links to view the articles themselves.)

My post (which is present entirely owing to the patience of Vu Thuy) “Ein Manifest der Freundschaft” is in honor of the August Macke und Franz Marc: Eine Künstlerfreundschaft exhibition (on through 3 May 2015 in the Lenbachhaus Kunstbau) and concerns one of my favorite subjects, the Paradies mural.

“Von »Köstlichen Figürchen« und »Wunderherlichen Farben«” by assistant curator Monika Bayer-Wermuth is actually the most wonderful post, though, on the gifts sent by the Marcs to the Mackes and is told in the same thoughtful, personal vein as are many of the chapters in the companion catalogue.

Thanks to the generous invitation of Arnold, I have two entries on her Notes About Art website, one called “Confrontations & Reconciliations” about my interpretation of Franz Marc’s gift of the painting Blaues Pferdchen, Kinderbild to August Macke and the other a bit about the history of Marc’s two Turm der blauen Pferde.

I am very happy to see art historians collaborating across distance and language just because we like the art and want for other people to be able to know about and appreciate the work of Der Blaue Reiter. (more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 21 Jan 2015 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, August Macke, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Helmuth Macke, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

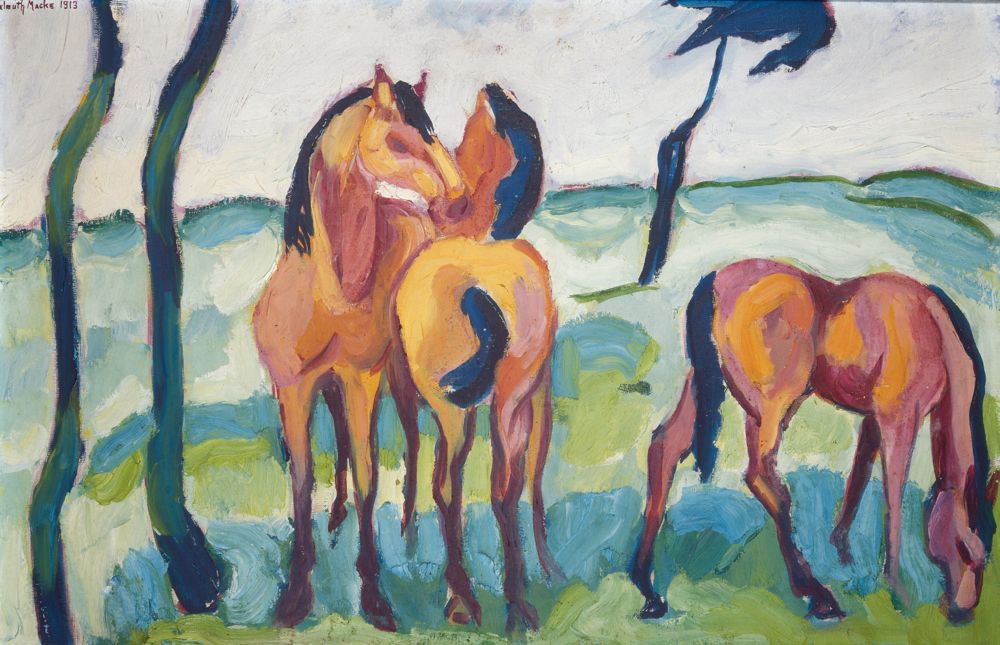

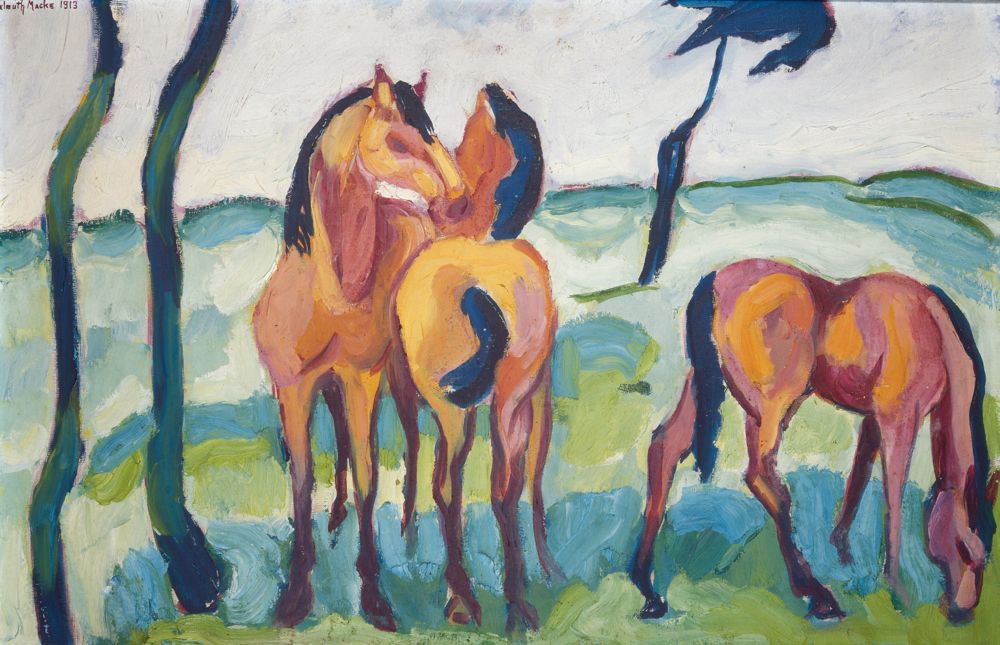

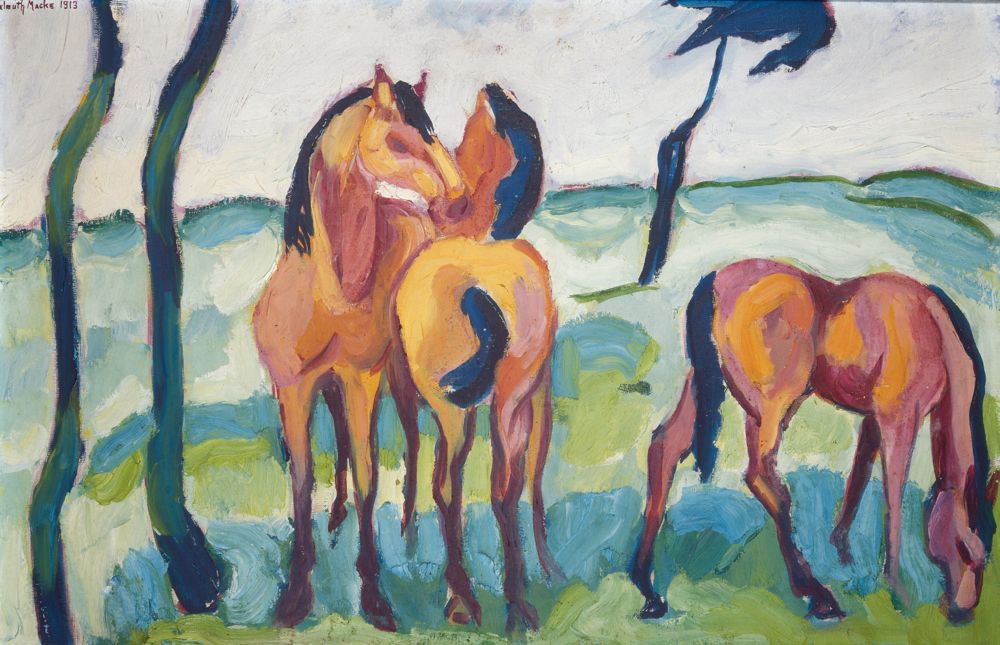

Helmuth Macke,

Drei Pferde,

1913

“The ‘boarding school’ is in session,” Franz Marc wrote nervously to his friend August Macke.[1] Pining for company in the same letter, Marc nonetheless wondered if August should come and get Helmuth Macke, August’s young cousin, whom the Macke family had deposited some weeks earlier at Marc’s small apartment in rural Sindelsdorf. It was late November 1910. Marc would soon turn 31, and Helmuth was 18. Until Helmuth’s arrival, Marc had been working alone for some time. At the insistence of her concerned parents, Maria Marc had returned to Berlin. Marc was just beginning to see the slightest of incomes from his painting, but he was irritable and distracted. And now August, himself adjusting with his wife Elisabeth to the birth of their son, expected Marc to find ways to entertain a teenager.

Yet Helmuth was resourceful and clever. During the weeks in Sindelsdorf, (which become months and longer: “Helmuth’s fine, he’s still growing,” Marc reported the following summer)[2], Helmuth taught himself enough Dutch to communicate with Heinrich Campendonk; chopped wood and built a fence; practiced painting and drawing, befriended Marc’s dog Russi; and demonstrated a talent for cooking and baking. This latter skill commanded Marc’s particular favor. Animated but sympathetic, Helmuth provided stability and encouragement. By Christmas Marc had breezily informed August that Helmuth would be staying on.[3]

As the calendar turned to 1911, the chrysalis of Sindelsdorf opened and released a new Marc to Munich. Seeking a sophisticated way to celebrate New Year’s, Helmuth pointed Marc toward a performance of Arnold Schönberg quartets. The music had a vivid impact on Marc, which he reported with great excitement to Maria, August, and a new friend who had missed the concert – Wassily Kandinsky. At a the soirée given by Marianne von Werefkin at which Marc and Kandinsky met at last in person, Helmuth was at Marc’s side, and witnessed the twinkle in the eye of fate that became Der Blaue Reiter.[4]

After the party, Helmuth and Franz took the late train from Munich to Penzburg, laughing and marveling over their adventure as they walked jauntily through the falling snow back to Sindelsdorf. Neither traveler was concerned for the future at that joyful moment, and mercifully, neither could know what the future held.

Helmuth Macke died in 1936 when his small boat capsized in a sudden storm on Lake Constance, having given his sailing companion the only life preserver.

[1] Franz Marc, August Macke: Briefwechsel. (Köln: DuMont, 1964), 20-21.

[2] Marc and Macke: Briefwechsel, 42.

[3] Marc and Macke: Briefwechsel, 28.

[4] Dominik Bartmann, Helmuth Macke, (Recklinghausen: Verlag Aurel Bongers, 1980), 26.

by Jean Marie Carey | 15 Dec 2014 | Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism

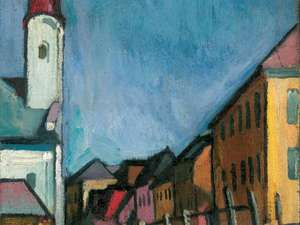

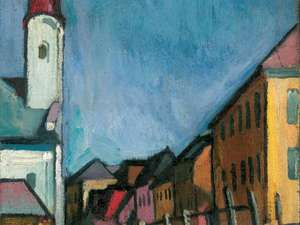

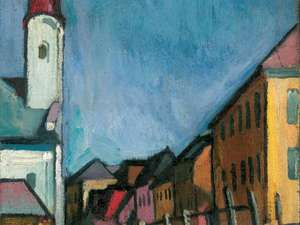

Is this colorful village scene painted by August Macke?

I have been working on a project about authenticating a painting maybe misattributed to one of my Expressionist painters (yet maybe made by another), so I was very interested to see a story crop up over the weekend in the Münchner Merkur online edition (pretty sure Süddeutsche Zeitung, usually so on top of all news Bayern, must be spitting nails!) about a man who thinks he owns a painting by August Macke.

Even more intriguingly, the painting would have been made in 1910, the year Macke spent in Tegernsee during which time Franz Marc often came to visit the Macke family, sometimes walking there through Oberbayern from Sindelsdorf to Tegernsee with Russi Marc. This period of time is recounted with warmth and in detail by Margarethe Jochimsen and Peter Dering in the book August Macke in Tegernsee.

The man who owns the painting, Herbert Spiess, claims to have purchased it from an art dealer in Vienna in 1984. Spiess told the Merkur he became convinced the painting, a small streetscape, was a Macke simply through visual association. (The Westfälische Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte in Münster says “no” in the Merkur’s story; no comment from the Lenbachhaus or the August Macke Haus in Bonn).

Macke enjoyed his time in Tegernsee. This was a happy year for Macke and his wife, Elizabeth and their first son, Walter, was born in the quiet lakeside village. Macke was more or less amused by his botany-obsessed landlords, whose Bayerische dialect he was able to penetrate with Marc’s help. Stubbornly autodidactic and much more fanciful and imaginative than he appeared at a glance, Macke spent hours doing “copying exercises” with Marc (and doing some other fun stuff too), and experimented with many styles of painting and drawing in 1910.

During this time, despite being in a very attractive location, Macke concentrated on portraiture, making many sketches and paintings of Walter, Elizabeth, and the famous portrait of Marc.

Bildnis Franz Marc, August Macke, 1910

But Macke also was always making all sorts of things, from tapestries to fabric designs to theater decorations. So it’s certainly possible this single painting is something he just knocked out during this period of great productivity – Macke was exceedingly prolific and made more than 200 paintings between 1909 and late 1910, when the young family returned to Bonn, leaving cousin Helmuth Macke to stay with Marc.

So it’s hard to say, from looking alone, if this painting could be Macke’s. I hope it is but (and this is really just a very strong intuition as much as empirical assessment) my feeling is that it might not be. To my eye the painting lacks that little flourish of passion and verve, and of capturing the “inner realities” of the beauty he was in the physical world, that is the beautiful Expressionist hallmark of Macke’s oeuvre. With any luck I’m wrong though, and the world will have a new August Macke painting to admire.

Anyway, the reporter, Vera Markert, asks that if you have any information or ideas about the painting to get in touch with the Merkur via email at kultur@miesbacher-merkur.de wenden.

by Jean Marie Carey | 15 Jun 2014 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

August Macke and Franz Marc packed the friendship of a lifetime into the few short years they had together from early 1910 to the summer of 1914, even with a few breaks for pouting and sulking. Some of their correspondence is recorded in a dedicated volume, and other letters, notes, stories, and recollections of their doings from other people are hidden in unpublished works and Expressionist apocrypha.

Macke and Marc enjoyed working on their art as a pair and in fact they both considered the drawings and sketches they made while just being together to fall into the class of “things we made together” on the same level as the few categorical objects to which we ascribe to their dual provenance, of which the mural Paradies, from 1912, is one. The mural lives now at the Westfalisches Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kultur in Münster, but it was made in the upstairs atelier of the Macke house (now the August Macke Haus ) in Bonn.

Given Macke’s constant scheming and hustling, and the sort of declarations of superficiality he seems to make about all that is admirable in painting, it is easy to think of him as being a sort of light shadow to Marc’s heavy element, but this is not at all true. And Marc often seems supremely naïve and dopey in his out-of-itness, which was also more of an occasional condition. However, the story attendant to the making of this mural finds them both in exactly these roles.

In fact as soon as I learned more about how Paradies was made, I immediately thought of the famous story in Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer printed below. In fact there is not much I can say about it, or as well.

Paradies, August Macke and Franz Marc, 1912

Excerpt from Tom Sawyer: Chapter 2

“Hi- yi ! You’re up a stump, ain’t you!”

No answer.

Tom surveyed his last touch with the eye of an artist, then he gave his brush another gentle sweep and surveyed the result, as before. Ben ranged up alongside of him. Tom’s mouth watered for the apple, but he stuck to his work. Ben said:

“Hello, old chap, you got to work, hey?”

Tom wheeled suddenly and said:

“Why, it’s you, Ben! I warn’t noticing.”

“Say — I’m going in a-swimming, I am. Don’t you wish you could? But of course you’d druther work — wouldn’t you? Course you would!”

Tom contemplated the boy a bit, and said:

“What do you call work?”

“Why, ain’t that work?”

Tom resumed his whitewashing, and answered carelessly:

“Well, maybe it is, and maybe it ain’t. All I know, is, it suits Tom Sawyer.”

“Oh come, now, you don’t mean to let on that you like it?”

The brush continued to move.

“Like it? Well, I don’t see why I oughtn’t to like it. Does a boy get a chance to whitewash a fence every day?”

That put the thing in a new light. Ben stopped nibbling his apple. Tom swept his brush daintily back and forth — stepped back to note the effect — added a touch here and there — criticised the effect again — Ben watching every move and getting more and more interested, more and more absorbed. Presently he said:

“Say, Tom, let me whitewash a little.”

Tom considered, was about to consent; but he altered his mind:

“No — no — I reckon it wouldn’t hardly do, Ben. You see, Aunt Polly’s awful particular about this fence — right here on the street, you know — but if it was the back fence I wouldn’t mind and she wouldn’t. Yes, she’s awful particular about this fence; it’s got to be done very careful; I reckon there ain’t one boy in a thousand, maybe two thousand, that can do it the way it’s got to be done.”

“No — is that so? Oh come, now — lemme just try. Only just a little — I’d let you , if you was me, Tom.”

“Ben, I’d like to, honest injun; but Aunt Polly — well, Jim wanted to do it, but she wouldn’t let him; Sid wanted to do it, and she wouldn’t let Sid. Now don’t you see how I’m fixed? If you was to tackle this fence and anything was to happen to it — ”

“Oh, shucks, I’ll be just as careful. Now lemme try. Say — I’ll give you the core of my apple.”

“Well, here — No, Ben, now don’t. I’m afeard — ”

“I’ll give you all of it!”

Tom gave up the brush with reluctance in his face, but alacrity in his heart. And while the late steamer Big Missouri worked and sweated in the sun, the retired artist sat on a barrel in the shade close by, dangled his legs, munched his apple, and planned the slaughter of more innocents.