by Jean Marie Carey | 25 Feb 2019 | Animals in Art, Art History, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Michelangelost©, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

Raubkunst at the Ringling…

…The Story Continues

Its genesis in 2016 was the glimpse of a fin becoming a feather that ignited a strong intuition at ”Raubkunst als Erinnerungsort,” a research fellowship sponsored by the Zentrum für Historische Forschung der Polnischen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Berlin that same December. Eventually, and with the help of many people, “Raubkunst at the Ringling” ran in the Modernism journal Lapsus Lima on 9 January 2019 and was picked up in the news all the way to the Antipodes that week with, for example, the story “Otago Link to Identifying Art Looted by Nazis.”

On 13 February 2019 I presented this research about Franz Marc’s woodcuts Schöpfungsgeschicte II (1914) and Geburt der Pferde (1913) amid colleagues at the College Art Association conference in New York City. The very next day I learned “Raubkunst at the Ringling” had been formally recognised as a “solved” case of Nazi looted art with the recognition of my findings by the Commission for Looted Art in Europe in the annals of The Central Registry of Information on Looted Cultural Property 1933-1945.

My hope all along has been that the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, the State Art Museum of Florida operated by Florida State University, would acknowledge the illicit acquisition of the prints by the American UPI reporter Robert Beattie from the notorious “Kunsthändler to the Third Reich” Bernhard A. Böhmer in 1940, prior to Beattie’s donation of them to the Ringling in 1956, where they have been hidden since, and allow these works to be shared with the public.

But wait: I have subsequently learned that there is potentially even more Raubkunst at the Ringling: Paintings by Christian Rohlfs and George Grosz and bronzes by Ernst Barlach with provenance gaps from 1933-1945 are also locked away at the museum as well as some oils and terracottas from the 16thand 17thcenturies that, while not entartete, were simply stolen or subject to forced “sales” from museums or private owners under the Reich.

To more fully bring this story to light, I would like to compile a volume – half catalogue, half detective story – about these works. Please do contact me if you are interested in working together on this project.

The only social media I participate in; this feed is mostly about art history and animals.

by Jean Marie Carey | 22 Sep 2017 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Dogs!, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism

My article related to Franz Marc and his dog, “To Never Know You: Archival Photos of Russi and Franz Marc” has been published in the Fall 2017 issue of Antennae: The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture.

Here is the abstract for the story about Franz Marc and his dog, which also contains some valuable personal insights on vernacular photography from other scholars and benefited from the questions and comments from my Doktormutter Cecilia Novero:

-

This essay examines photographs of the German Expressionist artist, writer, and Tierliebhaber Franz Marc and his dog, Russi, taking the position that one of the most obvious characteristics of Marc’s life his – affectionate and respectful relationship with Russi – has been largely overlooked, though its documentation is clear. I extol the value of what are normally categorised as snapshots in reconstructing animal and human biographies. This raises questions about what photographs are valuable to such research, and why some are used repeatedly and others ignored. Significantly, a previously unknown photograph of Marc taken by his brother Paul in is published for the first time.

Mainly I had wanted to write about discovering this photo of Franz Marc in the DKM/GNM, so here it is again:

Franz Marc, 1914, in Munich. Photo by Paul Marc. Germanisches Nationalmuseum | Des Deutschen Kunstarchivs | Nürnberg

by Jean Marie Carey | 7 Jun 2017 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Dogs!, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

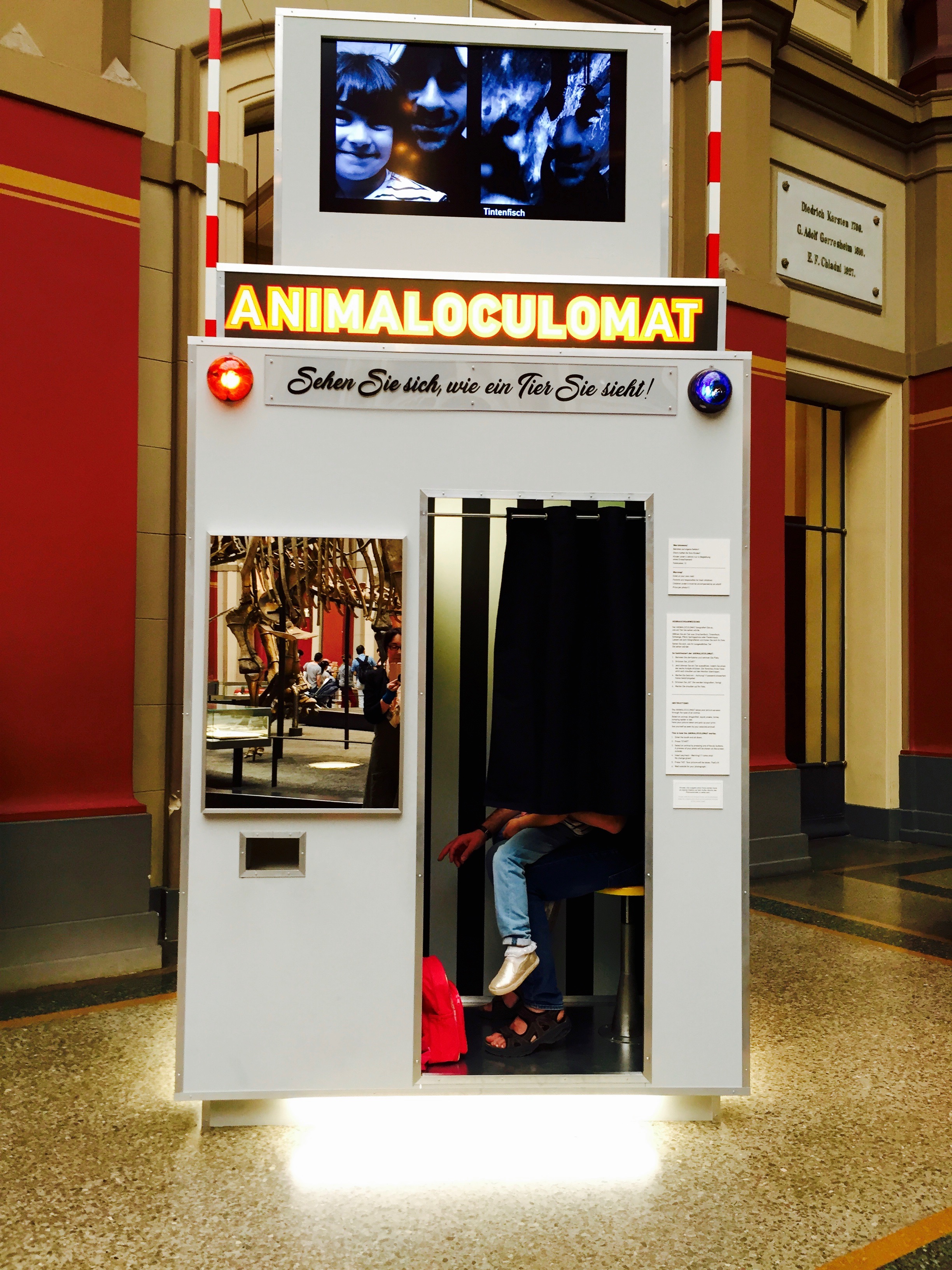

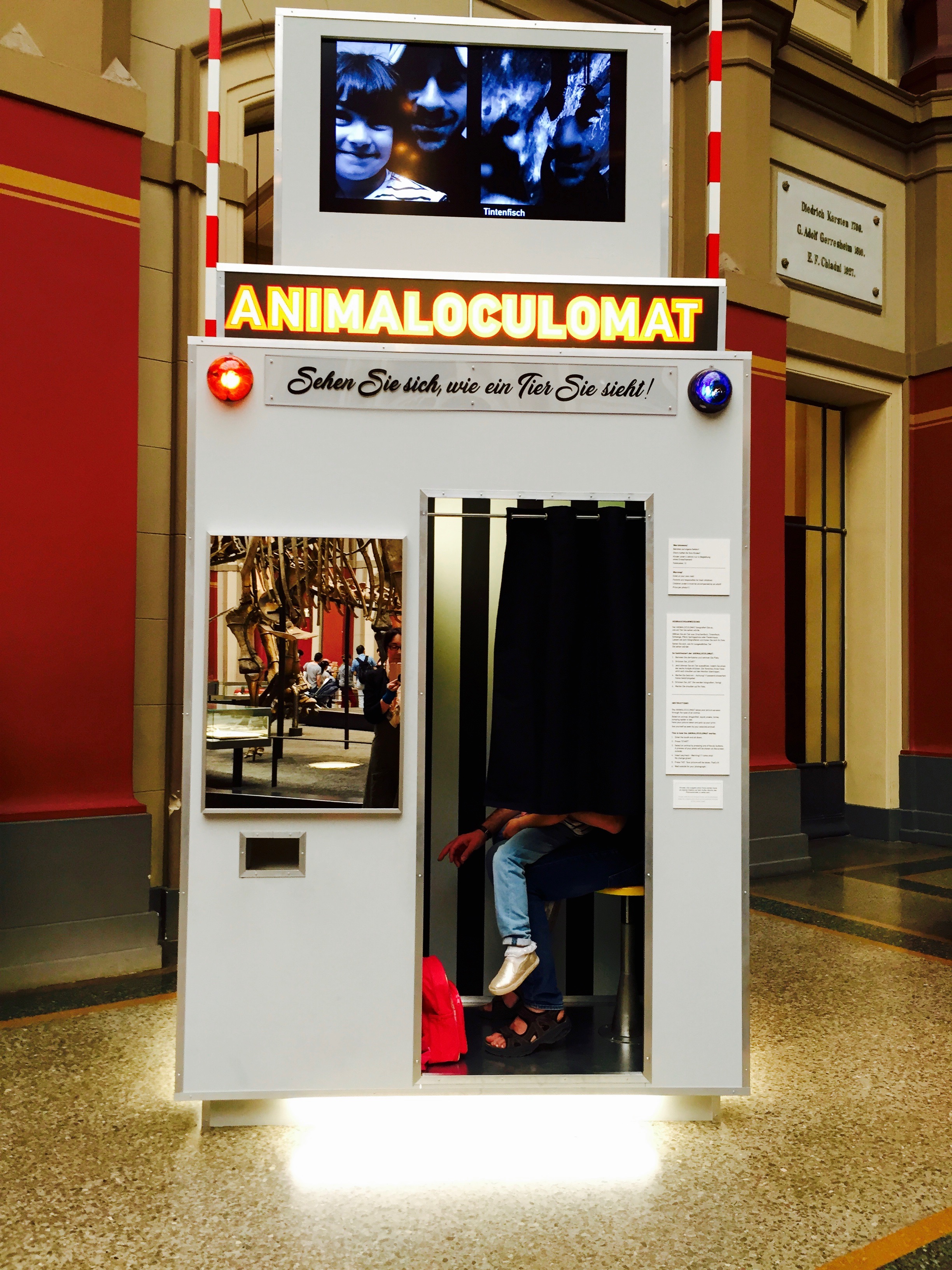

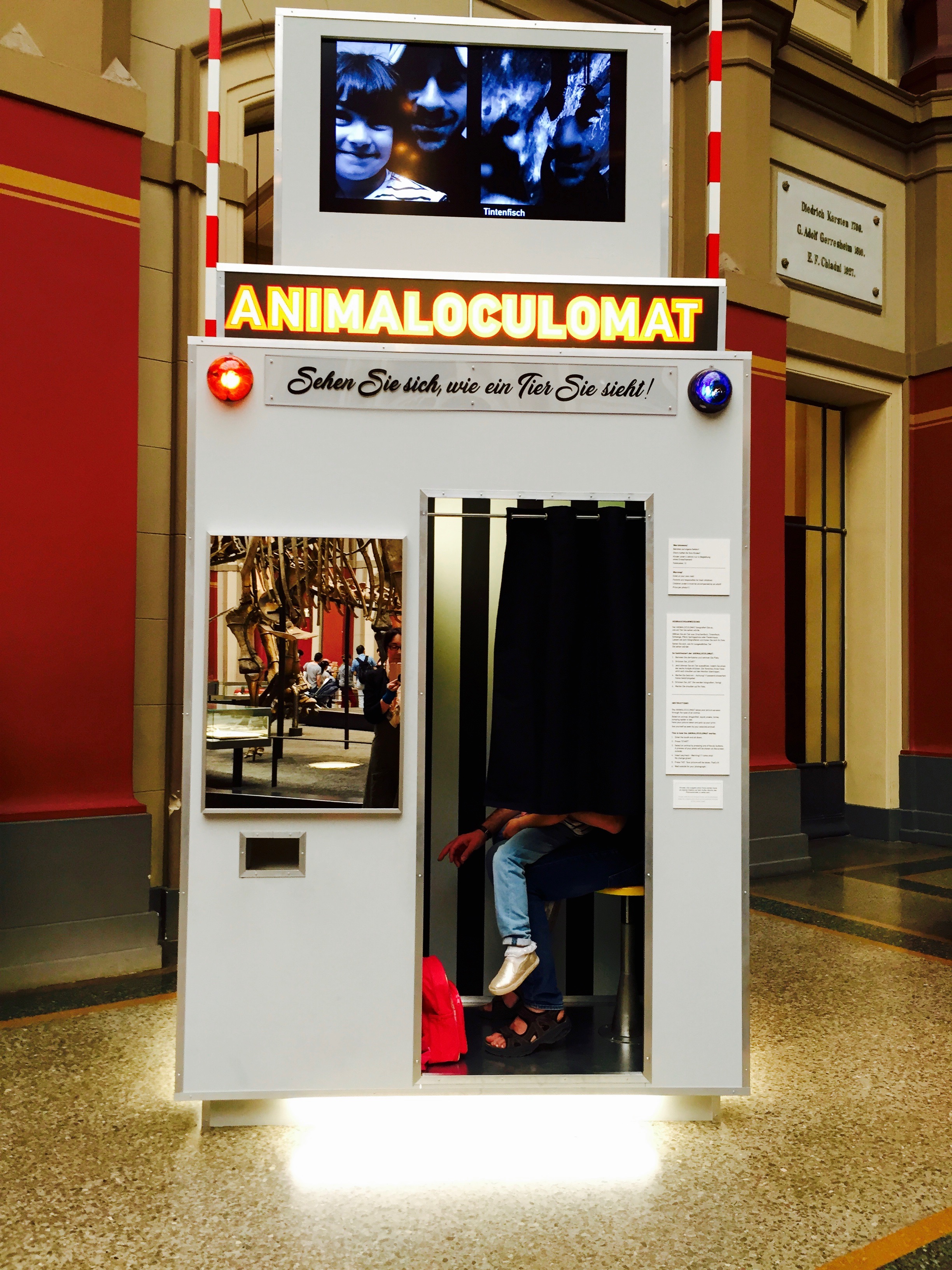

Klara Hobza, Animaloculomat, 2017

Already by 1909 Jakob Johann von Uexküll had, in Umwelt und Innenwelt der Tiere, given a great deal of consideration to the „Innenleben“ of animals. For Franz Marc this led to the question of how a horse, an eagle, a deer, or a dog saw and experienced the world, prompting the reflection „die Tiere in eine Landschaft zu setzen, die unsren Augen zugehört, statt uns in die Seele des Tieres zu versenken, um dessen Bildkreis zu erraten“.[1]

A painting like Liegender Hund im Schnee, a depiction of Marc’s dog Russi, radiates the oneness between the surrounding nature and the resting dog – „eine gemeinsame Stille von belebter und unbelebter Natur.“[2] .“ But Marc was interested in the actual physical reality of the dog’s vision as well.

Inside Klara Hobza’s Animaloculomat

by Jean Marie Carey | 3 Jun 2017 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

“Vermisst: Der Turm der blauen Pferde von Franz Marc” at Haus am Waldsee, Berlin

Marcel van Eeden, High Mountains, a Rainbow, the Moon and Stars, 2017

I really wanted to like Haus am Waldsee’s thematic “Vermisst: Der Turm der blauen Pferde von Franz Marc,” but was also nervous about all the expectations of the referenced Franz Marc painting that I would bring to the exhibition. To (un)prepare, I imposed a media blackout upon myself, not reading up on who the artists were or any other reviews,[1] avoiding a seminar and joint show co-sponsored by the Pinakothek der Moderne in München. Vermisst’s concept was to pair some scholarly discussions of Marc’s missing 1913 masterwork with the expansions of contemporary artists upon its theme.

Franz Marc Painting Still Missing

Beyond mild speculation, a purpose of Vermisst did not seem to be to offer any type of meaningful investigation into where the painting might actually be. It is not incumbent upon Haus am Waldsee, where the Franz Marc painting was last seen in 1949, to conduct such an inquiry…and yet the stubborn refusal, still, of German museums and art historians to grapple with the issue of Raubkunst, particularly in a case as famous as that of Turm der blauen Pferde, where someone knows something, is a real problem. (I have an article coming out on this very subject, so I’ll just leave this here for now.)

Of contributions by a dozen artists, one seemed to address both the absent presence of TdbP and also the circumstances of its disappearance. In fact if Marcel van Eeden’s High Mountains, a Rainbow, the Moon and Stars (2017), a series of 26 prints including the text of a short story revealing some fantastical open-ended conclusions about what happened to the painting, had been the only component of the exhibition, that would have been fine. Only two of Eeden’s panels are in color, both reproductions of aspects of TdbP, which makes a nice allusion to the Wizard of Oz (1939), both in temporality and in the vibrancy of the world of dreams, and of lost alternative futures. (more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 16 May 2017 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

This post goes with a book review of the exhibition catalogue Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim (2017) for Museum Bookstore which is posted here and also follows in a slightly different form below.

It has been one of life’s great pleasures to see Franz Marc’s Die gelbe Kuh many times over the years at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Every time I get the same huge surge of joy as the first, and I think other people feel the same way. When the painting is where it lives normally, in the Thannhauser wing, you can sit on a bench in the gallery and watch people come in, weaving their way through some much smaller woodcuts and decorated books, and then turn the corner to be met by this enormous colourful and cheerful painting. Always a lot of oohs and ahhs and delighted small children.

§ § §

People admiring Franz Marc’s Stallungen (1913, l) and Die gelbe Kuh (1911) at the Guggenheim.

Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim

Edited and introduced by Megan Fontanella with chapters by Vivien Greene, Jeffrey Weiss, Susan Thompson, Tracey Bashkoff, Lauren Hinkson, and Susan Davidson and published by Guggenheim Museum Publications, this catalogue accompanies the eponymous exhibition held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City, 10 February-6 September 2017; 312 pages with color reproductions of all the paintings and sculptures from the exhibition plus archival photographs, illustrations, letters, and newspaper and magazine notices.

The “modernization” of European art around 1900 is usually associated with the evolution of line, color, and figuration toward abstraction, as manifested by Expressionism and Futurism. The fact that art collectors and dealers played an important role in codifying what we think of now as Modernism is brought to full light in the catalogue Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim, produced to coincide with the exhibition of the same name.

In fact the catalogue seems, at least at first glance, intent upon driving home the idea that art is a business, opening with the normally blank flyleaf emblazoned with corporate logos and an unprecedented “Sponsor Statement” by Francesca Lavazza, heir to the Lavazza coffee brand, the underwriter of the exhibition. However the scholarly contents are innovatively presented and well-researched, with five sections devoted to each of the “visionaries” (in this case being the collectors, not the artists), paired with a focus on one of the museum’s key acquisitions. An opening essay by the Guggenheim’s curator of collections and provenance, Megan Fontanella, introduces the scope of the exhibition and the historical circumstances that allowed American entrepreneur Solomon Robert Guggenheim to decide in the 1920s, after five decades dominating the U.S. mining industry, to become the world’s foremost collector and exhibitor of what became dubbed “non-objective” art. (42) As in the rest of the book, the introduction offers wisely-selected and superbly reproduced works from both the immediate exhibition and from other sources.

Of great interest are photos of the assorted collectors and dealers in domestic settings, surrounded by their objets, which are very revealing, perhaps beyond what is intended by their inclusion in a book that is an official history of the Guggenheim. It is impossible, for example, not to be vexed by the careless profligacy of Peggy Guggenheim, niece of Solomon and founder of the Guggenheim Collection Venice. She is shown on the terrace of an Île Saint-Louis flat, wearing pearls and sipping an espresso as the Nazi-occupied Paris of the 1940s falls away across the river, Constantin Brancusi’s Maiastra (1912) set perilously on the parapet beside her. (254)

In fact the catalogue is an outstanding exercise for those willing to read between its restrained lines. Taken this way, an excellent contemporized portrait of the Guggenheim’s co-founder and first director, Hilla Rebay, emerges. Fontanella and Susan Thompson dispense with the “female hysteria” characterization of Rebay as the occult-obsessed lover of painter Rudolf Bauer to focus on her acumen as a businesswoman and strategic positioning as a collage artist. Thompson shows Rebay’s collages – figurative portraits for the most part, more like mosaics made with bits of paper than Hanna Höch’s more associative and confrontational critiques of Weimar culture – as a distinct oeuvre outside the canonical avant-garde’s concentration on sculpture and painting.

Equally calculating and less sympathetic is Rebay’s outsize ambition as Guggenheim’s chief advisor and deal-maker. Fontanella reports:

Rebay […] did attend the notorious Entartete Kunst show in Munich in August 1937, fresh from the June establishment of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. The foundation would make important purchases from the ensuing German-government-sponsored degenerate art sales: [Wassily] Kandinsky’s Der blaue Berg (1908-09) and Einige Kreise (1926), and [Paul] Klee’s Tanze Du Ungeheuer zu meinem sanften Lied (1922) were among the works that entered its holdings this way in 1939 – works that might have been destroyed. (30)

…Or works that might have been returned to their rightful owners.

(more…)