by Jean Marie Carey | 7 Jun 2017 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Dogs!, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

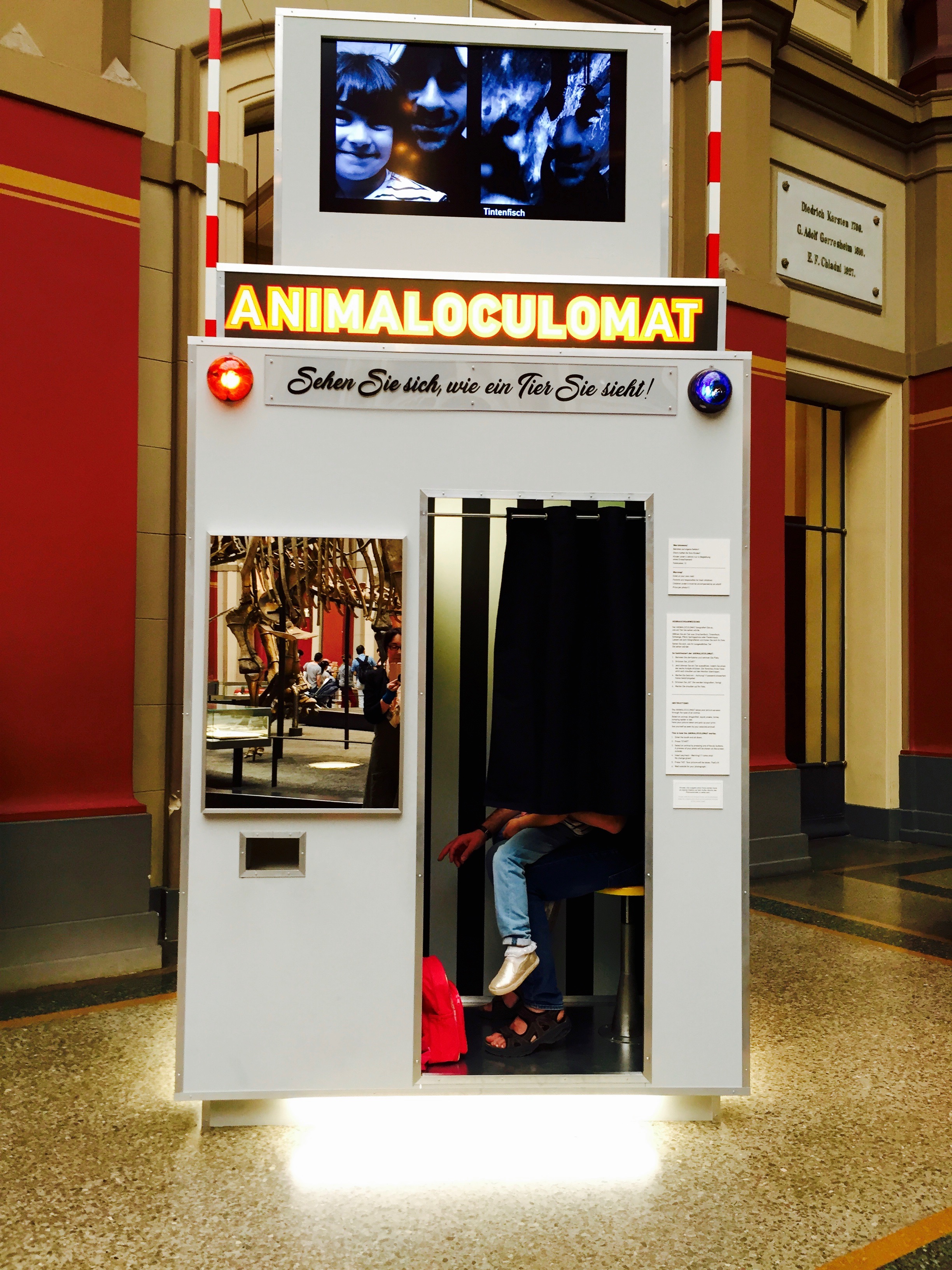

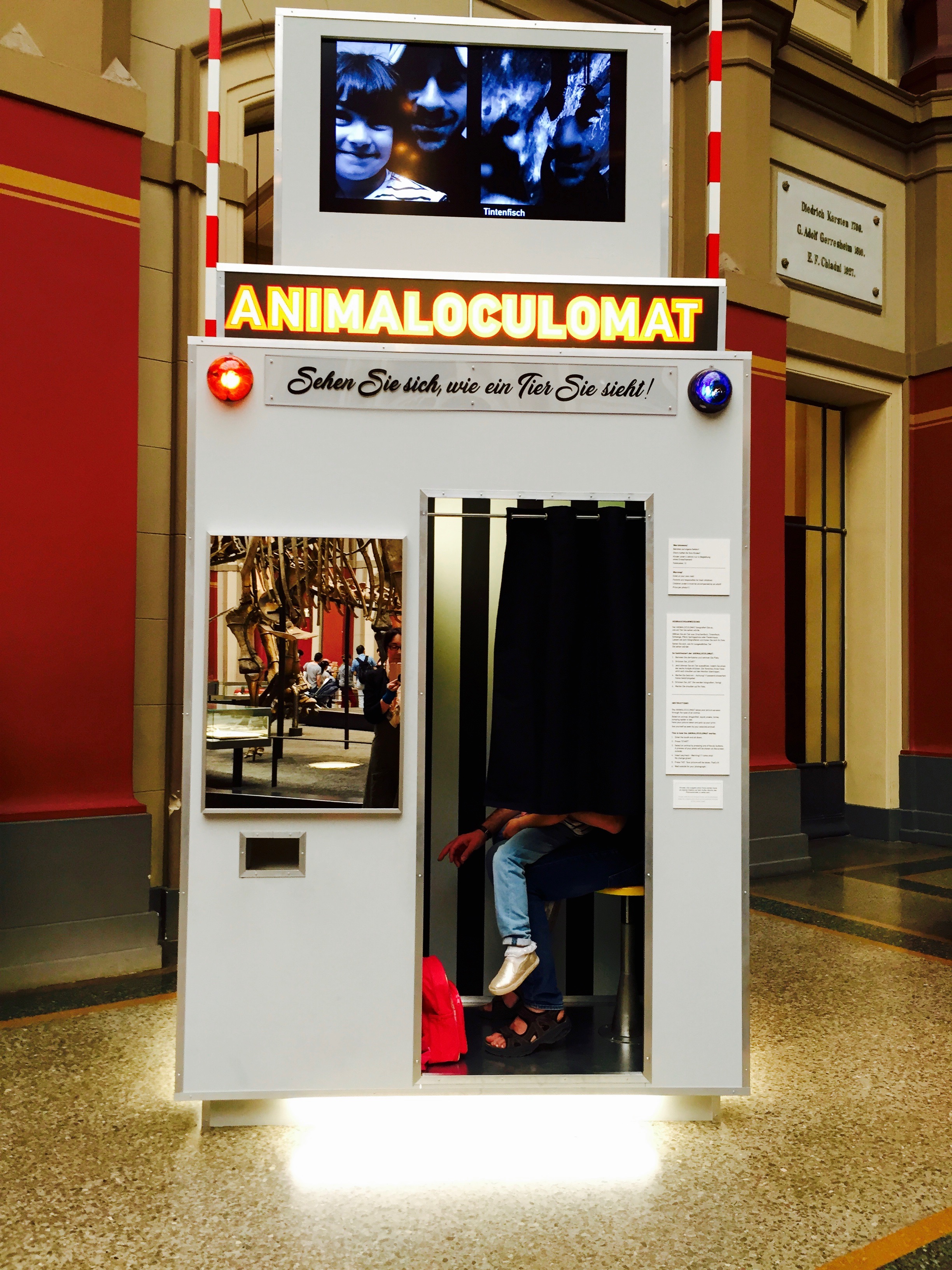

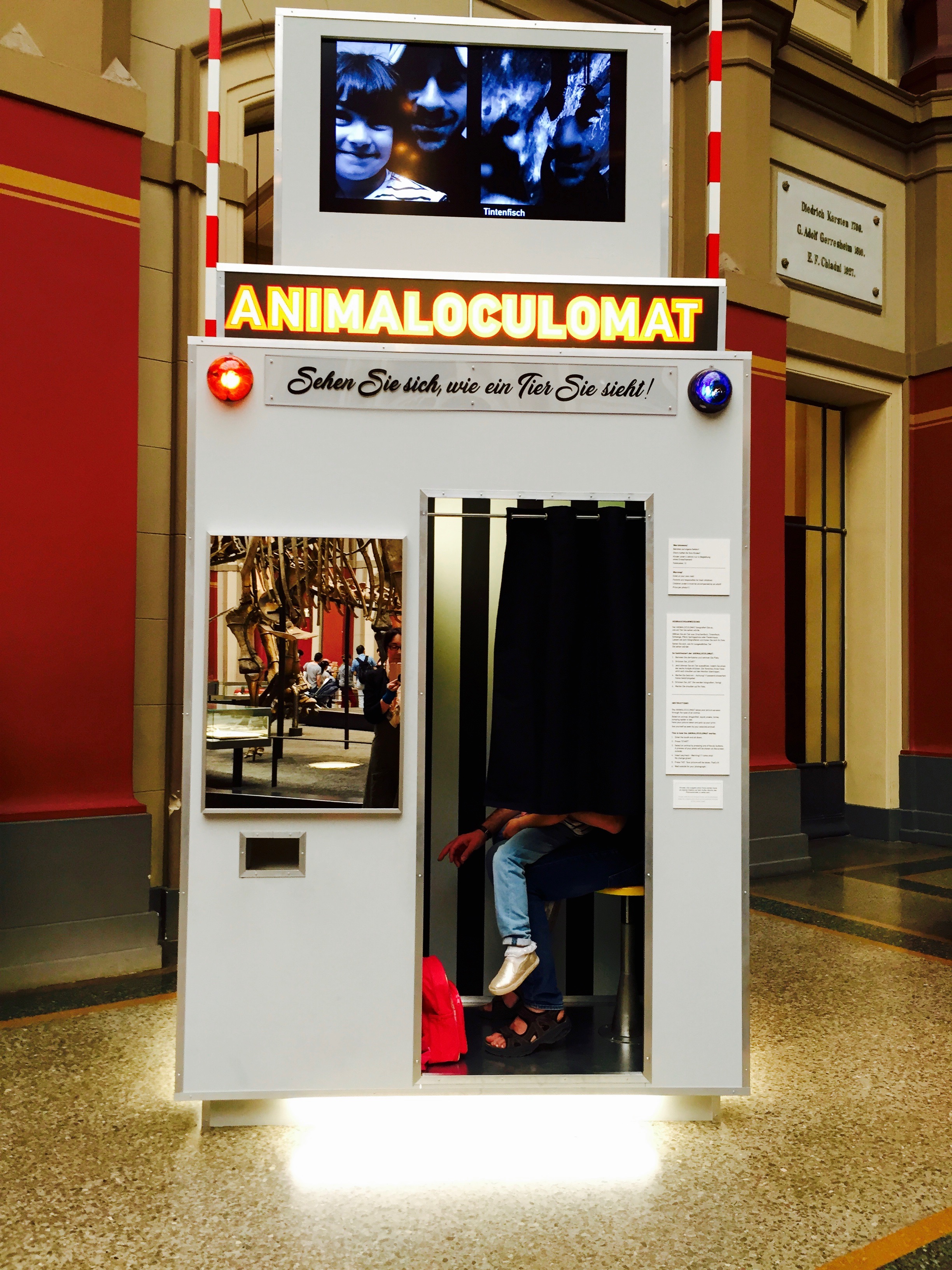

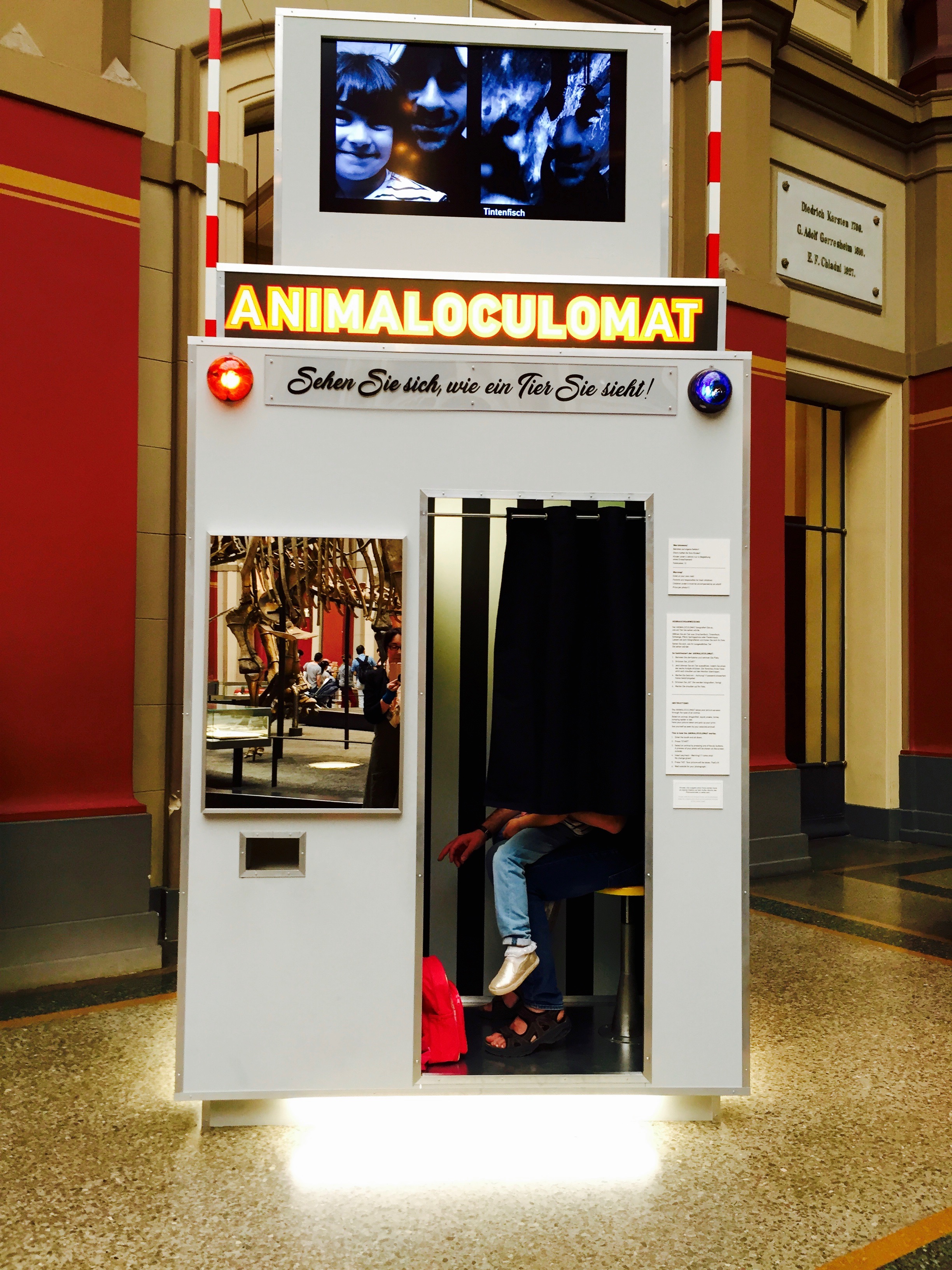

Klara Hobza, Animaloculomat, 2017

Already by 1909 Jakob Johann von Uexküll had, in Umwelt und Innenwelt der Tiere, given a great deal of consideration to the „Innenleben“ of animals. For Franz Marc this led to the question of how a horse, an eagle, a deer, or a dog saw and experienced the world, prompting the reflection „die Tiere in eine Landschaft zu setzen, die unsren Augen zugehört, statt uns in die Seele des Tieres zu versenken, um dessen Bildkreis zu erraten“.[1]

A painting like Liegender Hund im Schnee, a depiction of Marc’s dog Russi, radiates the oneness between the surrounding nature and the resting dog – „eine gemeinsame Stille von belebter und unbelebter Natur.“[2] .“ But Marc was interested in the actual physical reality of the dog’s vision as well.

Inside Klara Hobza’s Animaloculomat

by Jean Marie Carey | 3 Jun 2017 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

“Vermisst: Der Turm der blauen Pferde von Franz Marc” at Haus am Waldsee, Berlin

Marcel van Eeden, High Mountains, a Rainbow, the Moon and Stars, 2017

I really wanted to like Haus am Waldsee’s thematic “Vermisst: Der Turm der blauen Pferde von Franz Marc,” but was also nervous about all the expectations of the referenced Franz Marc painting that I would bring to the exhibition. To (un)prepare, I imposed a media blackout upon myself, not reading up on who the artists were or any other reviews,[1] avoiding a seminar and joint show co-sponsored by the Pinakothek der Moderne in München. Vermisst’s concept was to pair some scholarly discussions of Marc’s missing 1913 masterwork with the expansions of contemporary artists upon its theme.

Franz Marc Painting Still Missing

Beyond mild speculation, a purpose of Vermisst did not seem to be to offer any type of meaningful investigation into where the painting might actually be. It is not incumbent upon Haus am Waldsee, where the Franz Marc painting was last seen in 1949, to conduct such an inquiry…and yet the stubborn refusal, still, of German museums and art historians to grapple with the issue of Raubkunst, particularly in a case as famous as that of Turm der blauen Pferde, where someone knows something, is a real problem. (I have an article coming out on this very subject, so I’ll just leave this here for now.)

Of contributions by a dozen artists, one seemed to address both the absent presence of TdbP and also the circumstances of its disappearance. In fact if Marcel van Eeden’s High Mountains, a Rainbow, the Moon and Stars (2017), a series of 26 prints including the text of a short story revealing some fantastical open-ended conclusions about what happened to the painting, had been the only component of the exhibition, that would have been fine. Only two of Eeden’s panels are in color, both reproductions of aspects of TdbP, which makes a nice allusion to the Wizard of Oz (1939), both in temporality and in the vibrancy of the world of dreams, and of lost alternative futures. (more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 16 May 2017 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

This post goes with a book review of the exhibition catalogue Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim (2017) for Museum Bookstore which is posted here and also follows in a slightly different form below.

It has been one of life’s great pleasures to see Franz Marc’s Die gelbe Kuh many times over the years at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Every time I get the same huge surge of joy as the first, and I think other people feel the same way. When the painting is where it lives normally, in the Thannhauser wing, you can sit on a bench in the gallery and watch people come in, weaving their way through some much smaller woodcuts and decorated books, and then turn the corner to be met by this enormous colourful and cheerful painting. Always a lot of oohs and ahhs and delighted small children.

§ § §

People admiring Franz Marc’s Stallungen (1913, l) and Die gelbe Kuh (1911) at the Guggenheim.

Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim

Edited and introduced by Megan Fontanella with chapters by Vivien Greene, Jeffrey Weiss, Susan Thompson, Tracey Bashkoff, Lauren Hinkson, and Susan Davidson and published by Guggenheim Museum Publications, this catalogue accompanies the eponymous exhibition held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City, 10 February-6 September 2017; 312 pages with color reproductions of all the paintings and sculptures from the exhibition plus archival photographs, illustrations, letters, and newspaper and magazine notices.

The “modernization” of European art around 1900 is usually associated with the evolution of line, color, and figuration toward abstraction, as manifested by Expressionism and Futurism. The fact that art collectors and dealers played an important role in codifying what we think of now as Modernism is brought to full light in the catalogue Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim, produced to coincide with the exhibition of the same name.

In fact the catalogue seems, at least at first glance, intent upon driving home the idea that art is a business, opening with the normally blank flyleaf emblazoned with corporate logos and an unprecedented “Sponsor Statement” by Francesca Lavazza, heir to the Lavazza coffee brand, the underwriter of the exhibition. However the scholarly contents are innovatively presented and well-researched, with five sections devoted to each of the “visionaries” (in this case being the collectors, not the artists), paired with a focus on one of the museum’s key acquisitions. An opening essay by the Guggenheim’s curator of collections and provenance, Megan Fontanella, introduces the scope of the exhibition and the historical circumstances that allowed American entrepreneur Solomon Robert Guggenheim to decide in the 1920s, after five decades dominating the U.S. mining industry, to become the world’s foremost collector and exhibitor of what became dubbed “non-objective” art. (42) As in the rest of the book, the introduction offers wisely-selected and superbly reproduced works from both the immediate exhibition and from other sources.

Of great interest are photos of the assorted collectors and dealers in domestic settings, surrounded by their objets, which are very revealing, perhaps beyond what is intended by their inclusion in a book that is an official history of the Guggenheim. It is impossible, for example, not to be vexed by the careless profligacy of Peggy Guggenheim, niece of Solomon and founder of the Guggenheim Collection Venice. She is shown on the terrace of an Île Saint-Louis flat, wearing pearls and sipping an espresso as the Nazi-occupied Paris of the 1940s falls away across the river, Constantin Brancusi’s Maiastra (1912) set perilously on the parapet beside her. (254)

In fact the catalogue is an outstanding exercise for those willing to read between its restrained lines. Taken this way, an excellent contemporized portrait of the Guggenheim’s co-founder and first director, Hilla Rebay, emerges. Fontanella and Susan Thompson dispense with the “female hysteria” characterization of Rebay as the occult-obsessed lover of painter Rudolf Bauer to focus on her acumen as a businesswoman and strategic positioning as a collage artist. Thompson shows Rebay’s collages – figurative portraits for the most part, more like mosaics made with bits of paper than Hanna Höch’s more associative and confrontational critiques of Weimar culture – as a distinct oeuvre outside the canonical avant-garde’s concentration on sculpture and painting.

Equally calculating and less sympathetic is Rebay’s outsize ambition as Guggenheim’s chief advisor and deal-maker. Fontanella reports:

Rebay […] did attend the notorious Entartete Kunst show in Munich in August 1937, fresh from the June establishment of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. The foundation would make important purchases from the ensuing German-government-sponsored degenerate art sales: [Wassily] Kandinsky’s Der blaue Berg (1908-09) and Einige Kreise (1926), and [Paul] Klee’s Tanze Du Ungeheuer zu meinem sanften Lied (1922) were among the works that entered its holdings this way in 1939 – works that might have been destroyed. (30)

…Or works that might have been returned to their rightful owners.

(more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 7 Apr 2017 | Art History, Dogs!, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

Ars Graphica is a group of mostly European scholars who study prints but also photography. The pan-European organization also has a few Gesamtstaaten. Ars Graphica Deutschland recently branched off and began its own activities. The first one was this week, a tour of the In die Dritte Dimension: Raumkonzepte auf Papier vom Bauhaus bis our Gegenwart exhibition at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt given by the curator, Jenny Glaser. You can read more about what transpired here.

Dr. Glaser has organized a really superb show. The low and direct lighting is a bit off-putting at first, but many of the works are cut-outs, collages, incisions, or have subtleties of depth that the creation of shadows augments. The El Lissitzky poster prints from the Bauhaus are the stars of the show and Glaser’s clear favorite, but the less-known miniatures (matchbox sized) by Blinky Palermo placed across from Sol LeWitt’s late (2001) colorful confetti collage are probably more interesting, as is Michael Riedel’s artist book of minute but deep surgical removals.

There was also a look at the Städel’s more traditional Renaissance and Early Modern prints, and we got to visit and share a bit about our research…of course I have a vested interest in something at the Städel that is not a print…

I thought it might be best to just tell the exciting but short story about Liegender Hund im Schnee‘s journey from the Franz Marc estate to entartete to West Palm Beach and back to the Städel. Somehow the actual Germans were able to refrain from exclaiming that “all Germans are Nazis so who really cares if the museum was looted?”*

*Actual crowd responses at two of my last talks. More on this, as I keep promising, shortly; I actually have quite a lot to say about this in reference to the College Art Association in particular and looting apologists in general.

by Jean Marie Carey | 19 Sep 2016 | Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

SINTRAX Kaffeebereiter, 1932, Gerhard Marcks.

August Macke, Stillleben mit Tulpen, 1912

First I would encourage you to just skip this text and go right to the photos!

Otherwise: I went to Animalia: Interdisciplinary Perspectives and Explorations at the beginning of September mostly to see what the undergraduates and MA candidates were working on. The animal studies program at Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg is based within the Institute for American / English Studies. Though there was a mix of literary and cultural Human Animal Studies at hand the distinctive approach of this program is to examine the discipline through gender studies.

A highlight of the trip (in fact I devoted a whole day and night and went back the next day for this little side excursion) was visiting the Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte Oldenburg which is actually three buildings: Oldenburger Schloss, Augusteum, and Prinzenpalais; devoted to regional history, international “Old Masters,” and modern art, respectively.

The museums were fantastic in showcasing some artists you hear less about, or in prominent placement of less-famous works by people who are very well-known. The outstanding discoveries for me were a mournful 1937 still life by Gabriele Münter called Puppe, Katz, Kind; a the cheerful small Stillleben mit Tulpen by August Macke (which I think might be unfinished; it is very uncharacteristic in its facture of his work at this time) from 1912; Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s early Grace (1905); the subdued placement of Kurt Lehmann’s Sinnender Knabe (1948), who had a lot to think about, and a delightful whirligig coffee making device from Gerhard Marcks’s highest Bauhaus phase in 1932.

-

-

Wilhelm Lehmbruck, “Grace,” 1905.

-

-

Gabriele Münter, “Puppe, Katz, Kind,” 1937

-

-

Kurt Lehmann, “Sinnender Knabe,” 1948.

The Prinzenpalais is the collection that recently had its Max Liebermann Reiter am Strand (1909) returned to it, one of the most expeditiously executed rectitudes of the 2013 Cornelius Gurlitt recovery in München. The Prinzenpalais’s reaction to this turn of events seems strangely half-hearted, with just a small vitrine of the correspondence relating to Hildebrand Gurlitt’s involvement in the brokering the resale of the then-Entartete Kunst Reiter, and no explanation of the situational context really anywhere. I asked the docents if they were happy about having the painting back; they clearly weren’t all that happy, and doubly not to have someone ask informed questions.

Oldenburg has a nice Altstadt near the Landesmuseum but as middle-sized German cities go is somewhat difficult to get around in as it has only bus service, no UBahn or even a Straßenbahn or light rail system. Right now there is a lot of road construction with many ersatz Haltestellen and barricaded sidewalks, which the Münster- and Hamburg-aggression level Radler do not seem to be taking into consideration. Excluding Berlin, the farther north I go, the less I like it, and the more I recognize what a confirmed Südländerin I am.

-

-

Der H. Georg im Kampf mit der Drachen, c. 1512, Meister de Georgeschreins von Zwischenahn Eiche.

-

-

Das Wunderhorn, 1655, Fränkisch.

-

-

Hundekopf, Kopf des Zeus, c. 200 BCE, Tarent, Italien.

-

-

Franz Radziwill, Mosaik, 1948.

-

-

Scale mit Kauerndem Frauenakt, 1925, Rena Buthaud.

-

-

Bauhaus Schachspiel, “Model XVI,” 1924. Josef Hartwig.

-

-

Bauhaus Schachspiel, “Model XVI,” 1924. Josef Hartwig.

-

-

-

Franz Radziwill, Mosaik, 1948, Detail.

-

-

Zigarettendose, Gertrud Kraut, 1928.

-

-

Kinderschlitten um 1730.

-

-

Werbeplakat für Jugend, 1897.

-

-

Willem Claesz, Frühstücksstilleben, 1645.

-

-

Clutter.

-

-

Raum für Max Liebermanns Ölgemälde “Reiter am Strand” von 1909.

-

-

-

-

-

-

Max Lieberman / Kunst und Künstler.

-

-

Max Liebermanns Ölgemälde “Reiter am Strand” von 1909.

-

-

Dokumentation von Familie Gurlitt von Max Liebermanns Ölgemälde “Reiter am Strand” von 1909.

-

-

Dokumentation von Familie Gurlitt von Max Liebermanns Ölgemälde “Reiter am Strand” von 1909.

-

-

Jean Baptiste Pigalle, Merkur, 1785.

-

-

Detail of building.

-

-

Reneé Sintenis, August Gaul, Ewald Mataré, Richard Scheibe

-

-

Reneé Sintenis, August Gaul, Ewald Mataré, Richard Scheibe

-

-

Reneé Sintenis, August Gaul, Ewald Mataré, Richard Scheibe

-

-

Hans Hermann Weyl, Anneliese von Arnim als Kind, 1905.

-

-

Erich Heckel’s plate from Die Brücke catalogue…

by Jean Marie Carey | 28 Jul 2016 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

Franz Marc’s mysterious nude in a landscape from around 1911.

In clear contrast to the well-planned execution of the grazing horses on its front, the verso of Weidende Pferde IV is wild, mysterious, and haunting, and provides an intimate look at Franz Marc’s more intuitive approach to color and form.

Though the composition is partially obscured, the underlying motifs are clear enough.

Shown is a reclining female nude in a dimly lighted landscape under a deep blue sky. The figure rests on her back, her right leg is bent. Her head with long and flowing red hair is slightly tilted to the right; her arms clasped behind her. This figure is somewhat characteristic for Marc in terms of the visible hatching and decorated, colorful outlines. The left of the picture area seems to indicate another figure whose gender and position we can only guess at. The middle of the picture consists of a dramatic, deeply-hued landscape, which in turn is what the reclining nude in the foreground would be part of and also looking at. Though Marc often painted nude figures relaxing outside, this painting does not seem to correspond to another finished work.

Weidende Pferde IV, 1911

Weidende Pferde IV is also a stunning picture when considered in terms of Marc’s efforts to produce it: Three red horses with purple mane prance against a lemon-yellow sky and a deep blue rock formation. Marc had devoted a lot of time to developing the arrangement of the horses’ bodies in this formation. Marc had been preoccupied, and had made a difficult and lengthy process of, how exactly to balance the shapes and colors of the horses in the overall composition.

Weidende Pferde IV is the star of the second part of the exhibition trilogy “Franz Marc: Zwischen Utopie und Apokalypse,” presented by the Franz Marc Museum in Kochel on the 100th anniversary of the death year of the painter. This is one of just a few paintings that Marc saw hung in a museum himself, following its creation in 1911 and first display at the Thannhauser’s Galerie Moderne in Munich

The same year the collector Karl Ernst Osthaus purchased Weidende Pferde IV for the Folkwang Museum’s first incarnation in Hagen. The painting sold for 750 marks, as Marc triumphantly informed his brother Paul on 3 December 1911.

Marc had been constantly busy with live horses during his years in Kochel and Sindelsdorf (“Pferde auf Bergeshöh gegen die Luft stehend”), and he studied them in detail as he drew, printed and painted them.

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1909

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1910

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1910

The day before Alexej Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin and Adolf Erbslöh first visited Marc in Sindelsdorf on 3 February 1911, he wrote to Maria Marc who had at this time had left Bavaria to stay with her parents in Berlin, “Ich habe noch ein großes Bild mit 3 Pferden in der Landschaft, ganz farbig von einer Ecke zur anderen, angefangen, die Pferde im Dreieck aufgestellt. Die Farben sind schwer zu beschreiben. Im Terrain reiner Zinnober neben reinem Kadmium und Kobaltblau, tiefem Grün und Karminrot, die Pferde gelbbraun bis violett.”

The visitors loved the paintings, and by the day of his 31st birthday on 8 February Marc was a co-chairman of Neue Künstlervereinigung München.

Certainly the powerful painting of the reclining redhead should be regarded as an entirely discrete creation and given a proper name and place in the artist’s catalogue raisonné. It is curious that Harvard University’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, which purchased the painting when it was declared Entartete Kunst in 1937, has not taken the initiative to see that this is done. If only this painting could be permanently repatriated to Kochel, where it belongs.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts