by Jean Marie Carey | 12 Jul 2018 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Michelangelost©, Stuff Found in Library Books

Charles Maurice Detmold (1883-1908), Kestrel in flight, 1901. Watercolour. British Museum. Dept. of Prints and Drawings.

We, as mere humans, cannot see and feel as birds do as they navigate their habitats. Birds have immediate needs that relate directly to food availability, energy, water, and temperature, social contact, reproduction, predator detection, and shelter that are more complex than the features we perceive on their behalf as “nature.” Nevertheless, it is urgent for us to understand what bird species need from their surroundings as human intrusion, habitat loss, and climate change conspire to accelerate our need to make the best use of those habitats we can manage for the remaining populations of birds who survive. This is part of what makes Birds: The Art of Ornithology by Jonathan Elphick such a vital contribution to our historical knowledge.

A recent zoological conference in London featured a game of “Animal Studies Tic-Tac-Toe,” in which “David Attenborough” occupied a central square. Though the game was in jest, it is certainly true – and tellingly so that this is often the case even for those whose profession ostensibly involves the fauna of the wilderness – that for most people, the experience of nature is mediated by films such as those in the Life and Planet Earth series, augmented by precision editing, emotional cue music, and witty commentary.

Though not the overt intention of Birds: The Art of Ornithology, this book is a powerful reminder that connecting meaningfully with nature requires leaving the house, and that this experience is both transcendent and daunting. Birdwatching especially demands patience, silence, and solitude. Elphick conveys this foregrounding with subtlety, and describes the conditions faced by naturalists in the time before photography and video, who, tasked often only by their own passion – what John James Audubon characterized as “…nothing was left to me but my humble talents” – set out not only to observe birds but to record their activities and document their environments.

(more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 26 Jun 2018 | Animals in Art, Art History, Contemporary Art

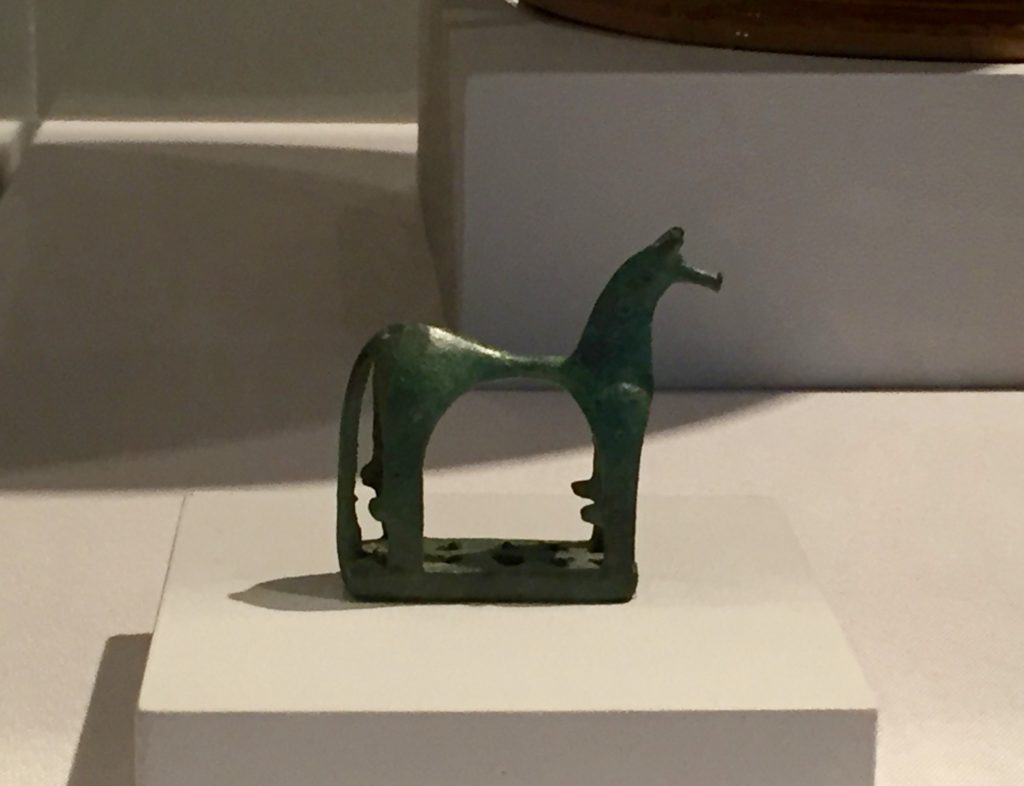

Possibly Etruscan horse, bronze, c. 3rd Century BCE

Over the summer I began writing for Arte Fuse with this review of Vapor and Vibration: The Art of Larry Bell and Jesús Rafael Soto at the Tampa Museum of Art. I quite like the show, and thought the curator was quite successful with this experimental pairing of two artists with no personal connection. It’s been so soothing to just sit quietly in the Animals in Ancient Art gallery at the TMA too, so I was sad to learn its last day is 1 July. The TMA also has a lovely collection of Etruscan mirrors.

While at the museum I saw for the first time some paintings of birds by Hunt Slonem. I got to observe many macaws in Miami and cockatoos, a nonnative species who have crossed the Tasman Sea to make themselves at home in New Zealand, are also very familiar. I thought the two paintings shown here used some interesting techniques to get to what’s essential about these clever and beautiful members of the parrot family. The focus on the pink tones and sociability of the cockatoos and of the strong beaks and feather structures of the macaws, absent their brilliant colors, is quite thoughtful.

-

-

Etruscan Mirror, c. 400 BCE, Tampa Museum of Art

-

-

Hunt Slonem, Habitat (Macaws), 1988.

-

-

Jesús Rafael Soto, Ambivalencia, 1981.

-

-

Larry Bell, XII HOJ, 2001.

-

-

Installation view, Vapor and Vibration: The Art of Larry Bell and Jesús Rafael Soto, Tampa Museum of Art

-

Until soon. – JMC

Hunt Slonem, Cockatoos, 2004.

by Jean Marie Carey | 20 Apr 2018 | Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

Franz Marc, Waldinneres mit Vogel (Taube), 1912.

Following below my reviews of two catalogues relating to the Hildebrand–Cornelius–Gurlitt bequeathal (artworks from the Gurlitt hoard) as has appeared on the Museum Books website and archived on Humanities Commons. First some digressions on the subject of Raubkunst.

One of the works recovered in Munich in 2012 you see here, Franz Marc’s Waldinneres mit Vogel (Taube) (1912). As in Die Vögel (also 1912 – I am just saying!) which lives at the Lenbachhaus, it is very hard to reproduce and thus to see the tone and hue of the violet Marc uses in these paintings about the avian experience. More on this soon, but hopefully you can get a bit of an idea of just how luminous and concatenate the purple and jades are in this canvas. Doubtful it can undergo conservation.

Franz Marc, Waldinneres mit Vogel (Taube), 1912, detail.

Both of these catalogues are very good, and I’m sure the forthcoming second part of the Gurlitt Status Report will be excellent too. (In another of the case’s amusing-macabre turns, these volumes are issued by the Hirmer Verlag, Hirmer, you may recall being the menswear hoarding store of choice of Cornelius Gurlitt. The companies are unrelated.)

But one of the things a scholarly work, at least under the present rules of publication, cannot capture is the intense emotion the discovery of the Gurlitt trove aroused in those who love the work – and not just art historians. One of the most intense experiences I had in Munich was the day in 2013 the Gurlitt seizure was revealed in FOCUS magazine. When the Süddeutsche Zeitung and Frankfurter Allgemeine began flashing notifications and tweets about the story at around 15:00 on 3 November, Schwabing’s ride-or-die Expressionism lovers (i.e. everyone in the neighborhood) literally ran out onto the streets both to steal a “just out walking” glimpse of the Gurlitt flat on the north side and to snatch up physical copies of FOCUS. I was fortunate to be on the U3 on the way to Schleißheimerstr already and just jumped off at the Olympiapark stop and, for once observing Bavarian queue rules, jostled my way up to the front of the news seller’s and grabbed the last one.

When I heard Simon Goodman speak at the Getty Research Institute this past March I was struck of course by his story, which is told in his book The Orpheus Clock: The Search for My Family’s Art Treasures Stolen by the Nazis (2015), but also by his marshaling of those powerful narrative and emotional resources that come from outside academic art historical presentation. You can view the whole talk at the Getty website.

Franz Marc, Waldinneres mit Vogel (Taube), 1912, detail.

First and foremost is the title: Who wouldn’t want to read a book called The Orpheus Clock, no matter what it was about? Goodman never wavers from the issue of provenance research that is in the foreground of the saga – if you watch the video you will hear Thomas W. Gaehtgens recount how Goodman quietly and unassumingly worked in the Getty library for years without revealing himself – but the story of the family, and the intrinsic value of the stolen and then recovered artwork, moves the narrative.

The other thing that strikes me, as my own Raubkunst at the Ringling project inches forward, is the cost of this kind of research, in every sense. For all his drive, patience, eloquence, and charm, Simon Goodman had a few advantages in his quest. But finally even the well-educated polyglot with many financial security, business, legal, and social connections could only use the threat of raining shame upon Sotheby’s and Christie’s to move them to reveal important information about the eponymous 16th Century silver and paintings by Cranach, Degas. Drive and weaponized publicity should not be the only avenues of retributive justice available. Systemic cooperation needs to lead.

Franz Marc, Sitzendes Pferd, c. 1912.

Look at this multimedia extravaganza! LOOK AT IT! LöL. Don’t ever tell me again FM isn’t funny.

The Gurlitt Hoard

In the wake of the revealed discovery in November 2013 of what has become known as the “Gurlitt hoard” – the thousands of artworks seized in a 2012 raid by the by German Federal, Bavarian State, and Munich police upon the Schwabing apartment of then 80-year-old Cornelius Gurlitt – a number of thoughtful and well-researched books have emerged, notably The Munich Art Hoard: Hitler’s Dealer and His Secret Legacy (2015) by Catherine Hickley.[1] Gurlitt, the peripatetic son of art dealer, gallerist, and sometime-curator Hildebrand Gurlitt, died in May 2014, bequeathing his collection to the Kunstmuseum Bern. The lifting of the embargo by a German court to allow Gurlitt’s trove to be dispensed to the museum was far from acclaimed – in fact, with many of the Gurlitt hoard works by 20th Century luminaries missing since the 1930s recovered from Gurlitt’s possession-jammed flat still of uncertain provenance – quite the opposite. Thus the museum of the city of Bern has been placed on defensive alert even while surely exulting over the acquisition of paintings, drawings, and prints by Franz Marc, August Macke, Henri Matisse, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and many others that greatly enrich our understanding of the historical avant-garde.

A Gurlitt hoard research catalogue and attendant exhibition was promised by the Kunstmuseum Bern, surveying the contents of its permanent collection as well for the presence of Raubkunst. And director Matthias Frehner kept his promise. The depth if not the scope of Modern Masters “Degenerate” Art at the Kunstmuseum Basel, the resulting publication, is even more ambitious than anticipated. lt offers a comprehensively illustrated checklist of the paintings from the Gurlitt acquisition as well as many other fascinating images and tales, from an account of the activities of patron-donor Othbar Huber to archival photographs rarely seen of Kathe Thannhauser and Herwarth Walden. However the excellent series of volumes Gurlitt Status Report: – Confiscated and Sold, Kunstmuseum Bern – Nazi Art Theft and Its Consequences, Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany (the second has just appeared – watch this space for updates) taking stock both more specifically and in consideration of the broader ramifications of the Gurlitt situation to some extent eclipses the Bern effort, launched from a collaborative co-exhibition at the Bundeskunsthalle Bonn.

(more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 9 Apr 2018 | Animals in Art, Art History

So, now that my time at the Rifkind Center is coming to an end, I have some breaking news announcements to post in sequence…

First, beginning this Saturday and through the summer months I will … well, be involved in a series of discussions about art history sponsored through a grant I received from the Hillsborough Public Library Cooperative. It’s all kicking off at the SouthShore Regional Public Library in Ruskin.

IKR

The SouthShore Library has a great history of funding arts programs for the patrons in its off-the-track corner of the county and I am very grateful to receive this support and for being able to work around upcoming travel obligations. The library staff had in mind a formal sequence of talks, but the proposal I made is for something more experimental that I have had in mind for a while…

…which is why I hesitate to call these “lectures.” Each session is going to be very interactive and will unfold in a participant-driven way, and there will be a digital component posted for downloading during and after each event.

(more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 27 Mar 2018 | Animals, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

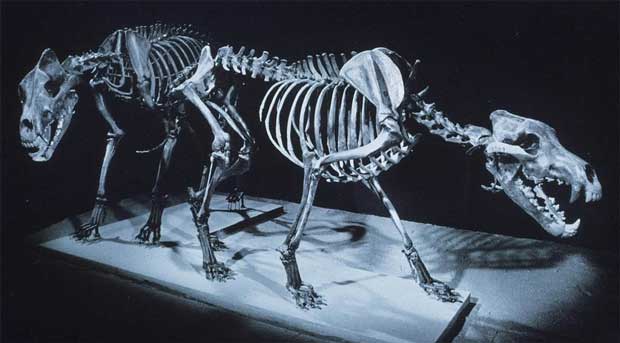

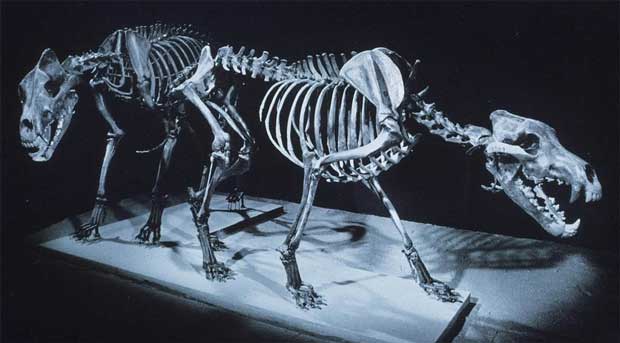

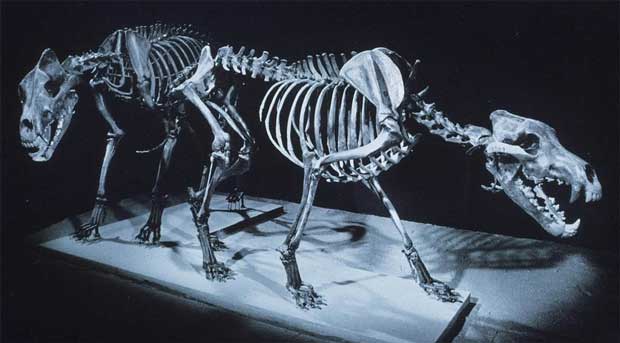

Skeletons of dire wolves at the La Brea Tar Pits Museum, Los Angeles

One of the first animals I became fascinated with when I was very little was the dire wolf (canis dirus). This was not for the “dinosaur” reason (although I was also very interested in Sauropterygia), a sense of what-if nostalgia for an unknowable past, but for the opposite, that being just a bit bigger than wolves of today, and relatively recently extinct (in the late Pleistocene, about 10,000 years ago) surely there could be a few hanging out still in the Fagne.

Around the same time I was also horrified to learn of the existence of the La Brea Tar Pits, despite its amazing contents of millions of prehistoric animal remains. I couldn’t stop thinking about all the animals slowly suffocating in the tar. I guess I must have pushed this memory aside somehow because despite knowing that the tar pits were right in the middle of Los Angeles (also from the famous sequence in Bad Influence (1990)), I was astonished to see that the LBTP are immediately adjacent to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Staying just down the street, I can walk through the excavation sites on my way to the museum. As many other people have commented the sunniness and wide-boulevardisation of Los Angeles compared to its low pedestrian density is uncanny already. Most of the time the paths around the tar pits are also eerily quiet. There have been a few days of heavy rain, and during those times of precipitation accumulation, water collects on top of the gravel, the grass, and the tar beneath. It’s a strange thing to witness.

Anyway the La Brea Tar Pits Museum has collected the skulls of more than 400 dire wolves, which yielding lots of information about the sizes and shapes of the animals and even allowed them to be divided into two subspecies, Canis dirus guildayi and Canis dirus dirus.

Bruce Nauman, “La Brea/Art Tips/Rat Spit/Tar Pits,” 1972